In many quarters, there is considerable resistance to the idea of international carbon trading. Some people characterize it as shipping money abroad for no reason, or the buying of ‘Hot Air.’ While there have certainly been problems with the implementation of carbon trading so far, the principle is intellectually sound. It could serve as a strong mechanism for reducing the total costs of climate change mitigation.

To understand why, consider that the major purpose of international carbon trading is to make tonnes of greenhouse gas emission reductions into a commodity. As such, their economic characteristics would be akin to those of other internationally traded commodities. Consider, for instance, an island state that requires copper for various purposes. It is technically possible to acquire copper on their territory, but the costs of doing so are enormous. Their copper reserves are dispersed and of poor quality, making the cost per tonne of finished copper excessive. Provided that the cost of buying copper internationally is lower than that of producing it domestically, the sensible thing to do is to buy the stuff on the world market. If the situation changes somehow (international prices rise, or foreign prices fall), the economically optimal choice may change as well. In the case of copper, this is immediately clear to virtually everyone. States that can produce copper more cheaply relative to other things sell copper internationally while those in the converse situation buy it. Both states with low-cost and those with high-cost copper benefit from this arrangement.

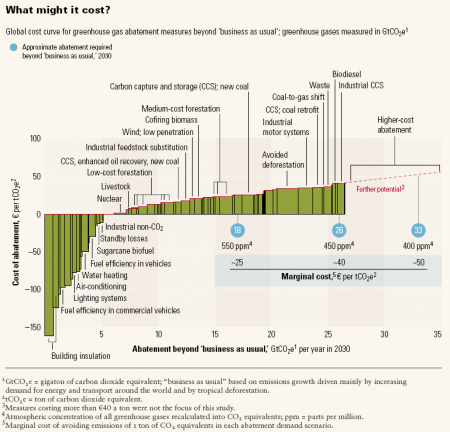

When it comes to carbon emissions, there are still comparative advantages that differ between states. This creates the possibility of positive sum trade: an exchange where both sides end up happier than they would be without trading. A relatively wealthy state that has already eliminated all the greenhouse gas emissions that can be easily forgone can pay a developing state to cut their own emissions. The buying state spends less than they would for producing the reduction domestically, and the receiving state gets the economic incentive to mitigate.

To reach this point, a few critical things are needed. First, for emission reductions to be tradable as a commodity, they must be measurable and verifiable. They differ from other commodities in that it is much more challenging to measure the tonne of CO2 a factory does not produce than the tonne of carbon that it does. That said, the difficulty is surmountable. We know how much greenhouse gas is produced by using different fuels in different ways. We also know how much is produced through different kinds of industrial production, such as cement manufacture. All that is required is the infrastructure and personnel to quantify and ensure reductions.

A trickier problem is that of additionality. If Country X pays Country Y $Z to build a natural gas power plant that will produce ten million fewer tonnes of CO2 than a coal power plant, it can only legitimately bank those tonnes if it was only the payment that motivated the choice. If Country Y actually chose the gas plant because coal plants pollute terribly and coal prices have been rising, Country X did not produce as many ‘additional’ reductions as intended. As with simple measurement, additionality is a practical problem that can be addressed through scientific and economic tools.

Developing and deploying those kinds of tools, so as to further the emergence of a robust and effective international carbon market, should be an excellent way to cut total human greenhouse gas emissions in a relatively rapid and low-cost way.