In the December 9th issue of The Economist, which I am just starting today, they come out against organic food, Fair Trade, and the idea that buying locally grown food is superior to relying on big retailers and large commercial farms (Leader and article). Organic food means producing lower yields for the same area of land: a big problem when you have a growing population and a desire to preserve wilderness. Fair Trade keeps farmers in poverty by encouraging farmers to keep growing commodities with volatile prices and low margins; moreover, most of the premium consumers pay goes to the retailer, rather than the farmer. As for local food, they say that large scale farming and food retailing produce food using less energy and resources (sheep are cheaper to farm in New Zealand and ship to the UK than to farm here). The solutions to problems like poverty and climate change, therefore, lie in carbon taxes, reform of agricultural trade policy, and the like.

Fair trade has always been a somewhat problematic concept, in my eyes. The whole basis for the legitimacy of exchange is in the process: the voluntary nature of the agreement means that both people who engage in it must perceive themselves to benefit. Now, there can be problems with this:

- The people may be wrong about what is in their interests

- Third parties may be affected

- The choice to trade may not be voluntary

All of these are real problems in many economic circumstances, but it is not clear why paying more for a label alleviates any of them. If we abandon the idea that the legitimacy of exchange is confirmed through its voluntarism, then we are left with the task of developing a comprehensive framework based on a teleological conception of justice (what people end up with, as opposed to how they get it). Even if that is desirable, achieving it is not simply a matter of paying a few more dollars a week for coffee or bananas.

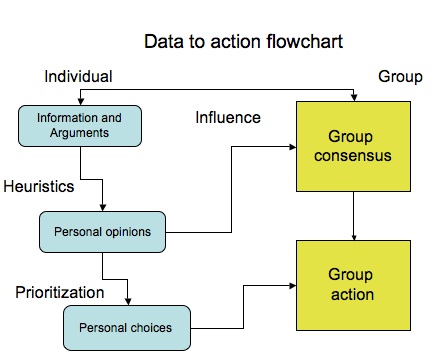

As for the problems with local and organic food, the issues there are primarily empirical and thus hard for me to evaluate. If the price of carbon emissions was included in that of food (and all other products), I would see little problem in eating tomatoes from Guatemala or apples from New Zealand. Similar criticisms are leveled in Michael F. Maniates’ interesting article Individualization: Plant a Tree, Buy a Bike, Save the World?. Maniates’ major point is that you will never get anywhere with a few token individual gestures. What is necessary is the widespread alteration of the incentives presented to individuals. Otherwise, you have a few people who salve their consciences by walking to work and buying from a farmers’ market, while not actually doing anything to address the problems with which they are supposedly concerned.

While the position taken by both The Economist and Maniates may overstate the point, both are worth reading for those who have accepted uncritically the idea that important change can be brought about through such ethical purchasing.

PS. Unfortunately, Oxford doesn’t have full text access to the journal Global Environmental Politics. If someone at UBC or another school could email me the PDF, it will save me a trip to the library and some photocopying costs, not to mention the integrity of the spine of their August 2001 issue. Here is a link to the page on their site for this article and another to a Google Scholar search that has it as the top hit.

[Update: 1:10am] A friend has sent me a much appreciated copy of the above requested PDF.