Over on the National Geographic website, there is a feature called The Daily Dozen, which consists of really excellent photography. The quality and originality of many of the shots is somewhat intimidating, though they are also an inspiration to improve one’s own efforts.

More disclosure for Canadian mining

Due to a recent federal court ruling, a long-standing disclosure exemption for the mining industry has been repealed. Previously, mining firms were not obliged to determine and disclose the toxic compounds present in their waste rock and tailings ponds. Apparently, environmental groups have been seeking to get rid of the exemption for sixteen years. American firms have had to obey similar disclosure rules for a decade now.

Data going back to 2006 will be made available on Canada’s National Pollutant Release Inventory (NPRI).

Obama’s Earth Day speech

It is heartening to see that Barack Obama has at least rhetorically accepted the fact that the fossil fuel industry has no long-term future:

Now, the choice we face is not between saving our environment and saving our economy. The choice we face is between prosperity and decline. We can remain the world’s leading importer of oil, or we can become the world’s leading exporter of clean energy. We can allow climate change to wreak unnatural havoc across the landscape, or we can create jobs working to prevent its worst effects. We can hand over the jobs of the 21st century to our competitors, or we can confront what countries in Europe and Asia have already recognized as both a challenge and an opportunity: the nation that leads the world in creating new energy sources will be the nation that leads the 21st-century global economy.

More from this speech is available on the Climate Progress blog.

While it is important to make people aware of the dire threat posed by climate change, and the gross immorality of not dealing with it, it is also vital to stress the opportunities associated. Foremost among them is the chance to shift society from dependence on harmful and dwindling stocks of fossil fuels to clean and inexhaustible renewable forms of power.

Baseload solar power

Albiasa Solar, a Spanish company, is planning a 200 MW concentrating solar plant in Arizona that will feature the capability of storing heat in molten salt, so it can continue to generate power throughout the night. The plant is expensive, with a cost estimated around $1 billion, but it will require no fuel and produce no waste. Hopefully, it will also provide experience that can be used to reduce the costs of such construction in the future.

All told, concentrating solar with energy storage is a very promising looking technology. It has many of the advantages of fossil fuel and nuclear plants, no fuel requirement, and good sustainability credentials. Plus, there is a lot of high quality solar land available in the southern US, as well as southern Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East.

Needless to say, this is a much more practical way to get 24-hour solar power than space-based systems would be.

Biofuels and nitrous oxide

In theory, biofuels are an appealing climate change solution. They derive the carbon inside them from atmospheric CO2 and their energy from the sun. They can be used in existing vehicles and generators, and store a lot of energy per unit of volume or weight. The raw materials can be grown in many places, without massive capital investment. Of course, recent history has given scientists and policymakers an increasingly clear understanding of the many problems with biofuels. A report (PDF) from Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE) of the International Council for Science (ICSU) concludes that, so far, biofuel production has actually produced more emissions than using fossil fuels would have. Partly, this is on account of the nitrous oxide emissions associated with the use of artificial fertilizers in agriculture. Over a 100 year period, one tonne of nitrous oxide causes as much warming as 310 tonnes of carbon dioxide. Corn produces especially large amounts of nitrous oxide, because it has a shallow root system and only takes in nitrogen for a few months each year.

It is possible that better feedstocks, agricultural techniques, and biofuel production processes will eventually make these fuels ecologically viable. Not all transportation can be electrified, and there will probably always be industrial processes that require petroleum-like feedstocks. Nonetheless, it must be recognized that the world has been going about biofuel production in the wrong way. That is something that should be borne in mind particularly by the citizens of states that are lavishing government support on them, both in the form of subsidies and by mandating that they comprise a certain proportion of transportation fuels.

Counting greenhouse gas emissions

Greenhouse gas emissions figures, as dealt with in the realm of public policy, are often a step or two removed from reality.

For instance, reductions in emissions are often expressed in relation to a ‘business-as-usual’ scenario, by governments wanting to flatter the results of their mitigation efforts. That means, instead of saying that emissions are X% up from last year, you say that they are Y% down from where they would have been in the absence of government action. Since the latter number is based on two hypotheticals (what emissions would have been, and what reductions arose from policy), it is harder to criticize and, arguably, less meaningful.

Of course, the climate system doesn’t care about business-as-usual (BAU) projections. It simply responds to changes in the composition of the atmosphere, as well as the feedback effects those changes induce.

The second major disjoint is between the relentless focus of governments on emissions directly produced by humans, compared with all emissions that affect the climate. For example, drying out rainforests makes them less biologically productive, leading to more greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere. Similarly, when permafrost melts, it releases methane, which is a powerful greenhouse gas. It is understandable why governments don’t generally think about these secondary emissions, largely because of the international political difficulties that would arise if they did. Can Canada miss its greenhouse gas mitigation targets because of permafrost melting? Who is responsible for that melting, Canada or everyone who has ever emitted greenhouse gasses? People who have emitted them since we learned they are dangerous?

While the politics of the situation drive us to focus on emissions caused by voluntary human activities (including deforestation), we need to remain aware of the fact that the thermodynamic balance of the planet only cares about physics and chemistry – not borders and intentionality. When it comes to “avoiding dangerous anthropogenic interference in the climate system” we need to remember to focus on both our absolute level of emissions (not their relation to a BAU estimate) and to take into account the secondary effects our emissions have. Doing otherwise risks setting our emission reduction targets too low, and thus generating climate change damage at an intolerable level.

Collecting bike statistics

Given that I am the kind of person who can be motivated by numbers, I decided to pick up a bike computer today – the simplest waterproof model available at MEC. After installing it, I wanted to make sure I had selected the correct wheel size (I think it’s 2174mm on the 700x32c wheels of my Trek 7.3FX). A few kilometres of cycling allowed me to confirm both its measure of velocity and distance traveled against my GPS receiver (a marine unit too big and cumbersome for cycling).

Unfortunately, it also confirmed that the little rare earth magnet that the sensor detects shifts around quite easily on my spoke, and it needs to be very carefully aligned to work. First, I tried gaffer tape, but it really wasn’t right for the job. Then, I tried the blogosphere, which suggested superglue. Glued in place, I hope that magnet isn’t going anywhere while I rack up the kilometres over the coming months.

For those keeping track, the trip out to get the computer, return home with it, and calibrate it amounted to 17.8km.

DVDs by mail

I am trying out zip.ca, a DVDs-by-mail system similar to Netflix. As such, I would appreciate if people suggested some films for me. I like the idea of having a big cue of random, interesting stuff and watching it in no particular order.

I have already requested Helvetica, Frost/Nixon, the third season of The Sopranos, and the second season of The Wire.

Fighting malaria with fungus

All the chemicals that human beings use to kill living things (weeds, bacteria, viruses) are subject to the same basic problem of resistance. A chemical that doesn’t manage to kill a few individuals will leave them with a huge opportunity to reproduce without competition. As such, all pesticides, herbicides, and antibiotics are likely to become less effective with time. Andrew Read, a Professor of Biology and Entomology at Penn State, is working on an approach for controlling malaria that circumvents this difficulty.

The mosquitoes that spread malaria are not born with the disease. Rather, they must bite someone who is infected. It then takes 10-14 days for the parasites to develop in the female mosquitoes, after which they reach the salivary glands and the insect becomes infectious. Read’s idea is to create a fungus that becomes lethal to mosquitoes after 10-12 days. As such, the fungus would exclusively kill the type of mosquitoes that infect people with malaria. The brilliant aspect of this is that the females will already have reproduced before being killed. That makes it far more difficult for genes resistant to the fungus to emerge and proliferate within the gene pool. That could make it an especially valuable tool in the fight against malaria – an illness that kills about one million people a year.

The idea is similar in some ways to the insect killing fungi described in Paul Stamets’ book, though his colony-exterminating approach seems like it would eventually breed resistance in a way that killing only older female mosquitoes would hopefully not do.

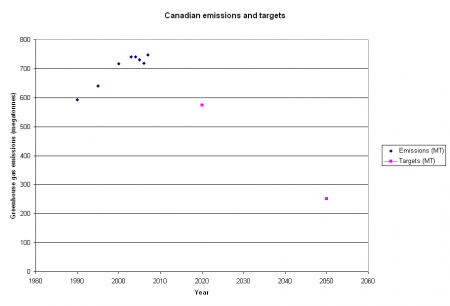

2007 Canadian emissions data

Back in May 2008, the figures for Canada’s 2006 emissions were released. They were made into a graph for a previous post. Now that the 2007 figures are available, the chart can be extended to show the 4% jump in emissions, putting Canada 26.2% above its 1990 level of emissions and 33.8% above its Kyoto Protocol target. In order to meet our target of cutting to 20% below 2006 levels by 2020, we will need to cut Canadian emissions by around 170 MT during the next eleven years.

The causes of the increase are also described:

“Between 1990 and 2007, large increases in oil and gas production – much of it for export – as well as a large increase in the number of motor vehicles and greater reliance on coal electricity generation, have resulted in a significant rise in emissions.”

Between 1990 and 2007, emissions rose by a total of 155 million tonnes (MT). 143 of those were from energy industries, including transportation and the oil sands. By contrast, residential emissions have basically been flat since 1990.