Theories for why the University of Toronto divested from fossil fuels

Not mutually exclusive:

- They are about to launch a bicentennial fundraising campaign with themes including healthy lives, sustainable future, and the next generation. They feared negative public relations attention if they launched the campaign while continuing to refuse to divest

- The university’s investment managers have decided that they can better retain authority and control by choosing how to divest on their own terms, and particularly with little reference to the culpability of the industry

- In trying to implement the prior environmental, social, and governance (ESG) screening method, the investment managers at the University of Toronto Asset Management (UTAM) corporation decided that divestment would be easier or better based on their secret internal metrics

- The Harvard announcement and COP26 have added to the pressure to announce new efforts

- U of T perceived that it was increasingly behind when a growing number of Canadian schools had made divestment commitments

- A student-led volunteer campaign persisted through multiple setbacks and core cohort graduations and was sustained by the University of Toronto Leap Manifesto chapter and subsequently the Divestment & Beyond faculty- and union-led campaign after the Toronto350.org / UofT350.org effort

As in the campaign as a whole, the university’s penchant for secrecy makes it challenging to explain or understand their actions. In particular, that includes the parlour trick of setting up your own investment management corporation as a means of evading oversight, by pretending that somehow the advice from this organization should only be available to the administration in secret.

Divest Podcast on the Leap Manifesto U of T divestment campaign

The latest episode of The Divest Podcast features Julia DaSilva from the Leap Manifesto chapter at U of T, the second of three groups to organize divestment campaigns, after the Toronto350.org / UofT350.org campaign and before / concurrently with the faculty/union Divestment & Beyond campaign.

Early environmentalism

The pro-carbon chorus at COP26

From today’s Globe and Mail:

- Efforts to combat climate change shouldn’t shun any particular energy source, Saudi official says

- Harper says Canada’s climate-change policy unfairly singles out ‘certain parts of the country’

I know Canada’s major media sources tend to be reflexively pro-fossil, but it’s still remarkable to see people insisting that the industries causing climate change should not be targeted as we try to keep it from destroying us.

Open thread: Urban thru hiking

Apparently it’s something that’s starting to exist:

Day hiking within city limits isn’t a new concept, of course. There are guidebooks detailing trails in cities from San Francisco to Atlanta. But Thomas has pushed the pursuit further, mapping out routes as long as 200 miles from one corner of a city to another and using infrastructure like stairways and public art to rack up elevation gain and provide something approximating a vista. She started in 2013 with a 220-mile through-hike in Los Angeles called the Inman 300, named for one of its creators, Bob Inman, and the initial number of stairways it included. Among other efforts, she has since hiked 60 miles through Chicago, 200 miles in Seattle, and 210 miles in Portland, Oregon. In 2015, she trekked the 54 miles from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, on the 50th anniversary of that historic civil rights march.

The way I see it, urban thru hiking lets you walk more comfortably with less gear since you never need to make camp. Routes that amount to a serious sustained hike can be added up from segments which avoid car traffic as much as possible, and which link up with public transit to let you get home at the end of the day and back at the trailhead easily the next one.

Related:

Summarizing and prioritizing

I got an insight on dissertation writing from the Spycast podcast’s interview with former vice presidential daily intelligence briefer Dave Terry:

This isn’t a be-all-end-all book. It’s a tailored 300-page briefing for senior faculty members. That perspective should help lessen the pain of cutting carefully researched content. It’s not that it’s bad, it just doesn’t belong in a briefing of this length and purpose.

Reading about the resistance dilemma

Today I received and began reading George Hoberg’s new book: The Resistance Dilemma: Place-Based Movements and the Climate Crisis.

The usefulness is threefold. It speaks directly to my concern about how the environmentalist focus on resistance isn’t a great match with building a global energy system that will control climate change. It references much of the same literature as my dissertation, so it provides a useful opportunity to check that I haven’t missed anything major. Finally, it’s an example of a complete, recent, and successful piece of Canadian academic writing on the environment and thus a model for the thesis. It’s even about 300 pages, though a lot more fits on a published book page than a 1.5-spaced Microsoft Word page in the U of T dissertation template.

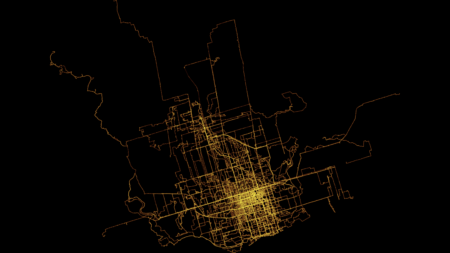

Pandemic walk heat maps

As part of playing around with my GPS data from my exercise walks since I wanted to make a heat map showing the likelihood of being in any particular place.

Here’s one I made using Seth Golub’s heatmap.py Python script (radius 5, decay 0.75):

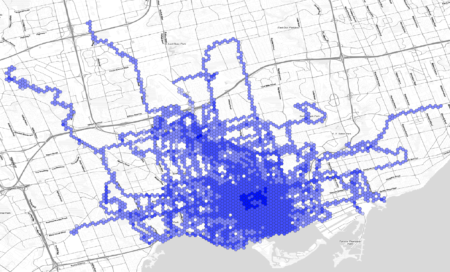

I also made one in QGIS. First I converted the tracks to a set of points in a CSV file. Then I created a spatial index of the point layer, created a hexagonal grid of polygons of a sensible size, and counted the number of points in each. Then I rendered that as brighter or darker hexagons:

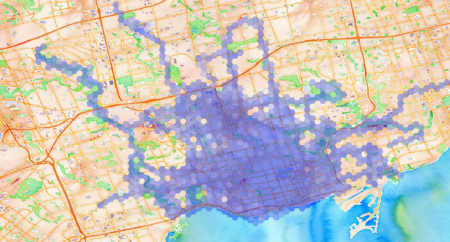

Here are the hexagons semi-transparent and rendered on a faux watercolour of the Toronto area:

The walks have sometimes been lonely and sometimes been scary, but they have been the main thing getting me out of the house and providing exercise during the pandemic. They do make me feel like I have a broader understanding of the city, though walking through a neighbourhood at night with headphones on only gives you a certain kind of perception.

Saying no to climate solutions

In This Changes Everything, Naomi Klein highlights the utility of a “Blockadia” strategy to keep fossil fuels in the ground through local land-based resistance campaigns. As George Hoberg raises in his latest book, and many others have discussed, the inclination of the environmental movement runs more toward stopping and preventing things than toward building solutions. For one thing, they get caught up in what I see as false narratives that corporations are exclusively to blame for climate change, or that somehow the world would be able to use drastically less energy. Environmentalists also tend to see any environmental impact as grounds for opposing a project. Impact on birds is a reason to resist wind; impact on the landscape is a reason to oppose solar; offshore wind may ‘mesmerize crabs.’ They point out that even if we bring climate change under control we will have problems with lost biodiversity, toxic pollution, and many other issues — and thus spread their skepticism about electric vehicles or battery power because of the mineral resource requirements.

All this leaves us in a position where environmentalists are accurately raising the alarm about climate change, while rarely suggesting a path forward for replacing that energy and for providing new energy to the parts of the world that are developing economically. As David MacKay put it at the end of his book:

Because Britain currently gets 90% of its energy from fossil fuels, it’s no surprise that getting off fossil fuels requires big, big changes — a total change in the transport fleet; a complete change of most building heating systems; and a 10- or 20-fold increase in green power.

Given the general tendency of the public to say “no” to wind farms, “no” to nuclear power, “no” to tidal barrages — “no” to anything other than fossil fuel power systems — I am worried that we won’t actually get off fossil fuels when we need to. Instead, we’ll settle for half-measures: slightly-more-efficient fossil-fuel power stations, cars, and home heating systems; a fig-leaf of a carbon trading system; a sprinkling of wind turbines; an inadequate number of nuclear power stations.

We need to choose a plan that adds up. It is possible to make a plan that adds up, but it’s not going to be easy.

We need to stop saying no and start saying yes. We need to stop the Punch and Judy show and get building.

If you would like an honest, realistic energy policy that adds up, please tell all your political representatives and prospective political candidates.

Global energy use is about 576 EJ (5.8 x 1020 J), and world electricity consumption to be about 63 EJ (6.3 x 1019 J). Giving all 7.7 billion people on Earth the 125 kWh/day energy use of the average European would require energy production of 962.5 billion kWh per day (3.5 x 1018 J), or 351.3 trillion kWh per year (1.3 x 1021 J). That’s equivalent to about 45,000 1,000 MW power stations. If we want to avoid climate change in a way that is at all politically plausible, we need to get building.

Related: