Another privacy spat has erupted in relation to Facebook, the social networking site. It all began when the site began actively advertising everything you did you all of your friends: every time a photo was updated or a relationship status changed, everyone could see it by default, rather than having to go looking. After that, it emerged that Facebook was selling information to third parties. Now, it seems that the applications people can install are getting access to more of their information than is required for them to operate, allowing the writers of such applications to collect and sell information such as the stated hometown and sexual orientation of anyone using them.

Normally, I am in favour of mechanisms to protect privacy and sympathetic to the fact that technology makes that harder to achieve. Facebook, I think, is different. As with a personal site, everything being posted is being intentionally put into the public domain. Those who think they have privacy on Facebook are being deluded and those who act as though information posted there is private are being foolish. The company should be more open about both facts, but I think they are within their rights to sell the information they are collecting.

The best advice for Facebook users is to keep the information posted trivial, and maintain the awareness that whatever finds its way online is likely to remain in someone’s records forever.

[Update: 12 February 2008] Canada’s Privacy Comissioner has a blog. It might be interesting reading for people concerned with such matters.

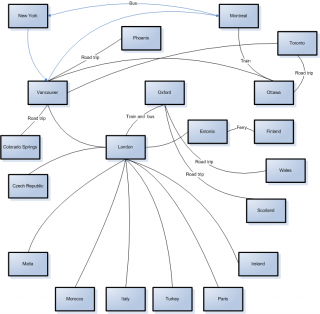

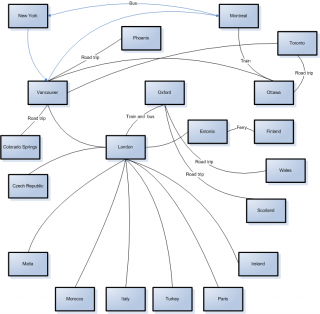

This graphic summarizes the travel I have done since 2000, with blue arrowed lines for one way trips and black lines for return journeys. Lines with no mode of travel indicated are flights. The chart is not completely comprehensive (it excludes relatively minor trips) and it is somewhat simplified, but it gives a good overall sense.

I hope I am lucky enough to see a similar amount during the next eight years, in spite of air travel guilt.

The other week, I bit the bullet and ordered one of Peter Atwood‘s excellent handmade tools. In anticipation of the summer, I ordered his bike tool. It’s about three inches long and made from Crucible‘s CPM3V cutlery steel, with a bead blasted finish. It includes 4mm and 5mm hex bits and a 15mm axle wrench, as well as a prybar. I have long admired Atwood’s work as quite beautiful but, prior to seeing the bike tool, never saw something well suited enough to something I do to justify the expense.

The appeal of the tool lies largely in the mode of manufacture. Virtually everything I have ever owned has been mass produced: clothes, electronics, furniture, tools, etc. Having something that was individually forged by a human being is fairly rare. All the logic of economics resists a production process wherein a single being completes everything from design through manufacturing to product testing, and yet it is strangely satisfying to possess something that arose from such an effort. It is that knowledge, and the value derived from it, that justifies paying a relatively high price for such an object.

All in all, this is one more reason I can’t wait for the roads to clear, allowing me to bring my bike up from the basement.

Something strange is happening to undersea fiber optic cables in the Middle East: they are being cut. At least four, and possibly five, of the communications links have failed in the last twelve days. The first two were allegedly damaged by a ship’s anchor; subsequent failures are more mysterious. Serious disruptions are being experienced in Egypt and India, along with lesser problems in Bahrain, Bangladesh, Kuwait, the Maldives, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. The fifth cable cut seems to have disabled internet access in Iran.

It’s tempting to ascribe some nefarious motive to all of this. That said, it is sensible to recall how past hysterias proved unjustified. After much hoopla in the media, it turned out that the ‘cyberwar’ against Estonia was the work of a twenty year old subsequently fined $1,620 for his misdeeds.

The cable problems are being widely discussed:

[Update: 16 February 2008] According to The Economist, all this was just hysteria.

The common account of ‘peak oil‘ is straightforward enough. Oil is a non-renewable resource; as such, every barrel taken from the ground means one less for the future. The depletion of current reserves is temporarily offset by the discovery of new reserves and the development of better technology to extract more oil from the reserves we know about. A higher price for oil stimulates both exploration and technological development, creating a negative feedback loop that, to some extent, moderates scarcity and long-run prices. Given the finite nature of oil, it is a logical necessity that extraction will eventually exceed new discoveries and technological improvement, provided we continue to extract oil. The controversial question is when this will occur. Some people argue it already has, others that it will not take place for decades. You have to be a real optimist to think we can continue to expand or maintain present levels of oil extraction for a century.

In the conventional story, the next fossil fuel in line is coal. This is bad for a lot of reasons, including the damaging nature of coal mining and the high pollution and greenhouse gas emissions associated with burning coal. At least, the conventional wisdom says, coal is plentiful. The American Energy Information Administration estimates that 905 billion tonnes exist in recoverable reserves: enough to satisfy the present level of usage for 164 years. The World Energy Council estimates reserves at a somewhat more modest 847 billion tonnes. Combining the idea of peak oil with the reality of dirty coal has led many environmentalists to fear a world where cheap oil runs out and people switch to coal, with disastrous climatic consequences.

An article in the January issue of New Scientist challenges this orthodoxy. The article argues that official reserves have fallen over the last 20 years to an extent far greater than usage, suggesting that the estimates were over-generous. It asserts further that the ratio of official reserves to annual coal extraction worsened by 1/3 between 2000 and 2005. This is attributed primarily to increased demand in the developing world.

The article predicts that the combination of higher rates of usage and smaller than stated reserves may cause oil to “peak as early as 2025 and then fall into terminal decline.” If this is true, it massively changes the logic of coal power and carbon capture and storage. The only reason anybody wants to use coal is because they perceive it to be a relatively inexpensive and amply provisioned fossil fuel that can be obtained from stable and friendly countries. If coal plants being built today with a fifty year lifespan are going to face sharply increased feedstock prices in a few decades, their economic competitiveness compared to renewable energy may be non-existent. This is especially true of plants with carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology, since they require about 20 to 40% more fuel per unit of electricity, in order to power the separation and sequestration equipment.

One article does not make for a compelling case, especially given the poor overall record people have had of predicting energy trends and prices across decades. The article acknowledges the scepticism surrounding the idea of peak coal:

The idea of an imminent coal peak is very new and has so far made little impact on mainstream coal geology or economics, and it could be wrong. Most academics and officials reject the idea out of hand. Yet in doing so they tend to fall back on the traditional argument that higher coal prices will transform resources into reserves – something that is clearly not happening this time.

Regardless of whether this particular analysis proves to be accurate or not, it does a service in questioning an important assumption behind a fair bit of energy policy planning. The idea of peak coal has a complex relationship with climate change. On one hand, it might reduce the incentive to develop CCS, making whatever coal is burned more climatically harmful. On the other hand, awareness that coal reserves are more limited than assumed might prompt more investment in renewable energy, the only option that is sustainable in the long term.

Even if world coal reserves are significantly smaller than the official estimates above, there is a good chance that burning all that is available will have extremely adverse climatic consequences. We know the approximate level of emissions that would maintain stable atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gasses and we know that we are way above it. What we don’t know is the shape of the damage curve associated with increased concentrations, increased radiative forcing, and further increased mean temperatures. Even if there aren’t sharp transitions within the next 150 ppm or so, it is inevitable that extensive further use of coal will push us further into unknown and potentially dangerous territory.