Month: November 2017

Inside sculpture

Ethics protocol going for full review

On October 10th I submitted the proposed research ethics protocol for my PhD research to the University of Toronto’s Office of Research Ethics.

My committee thought that the subject protection risks were minimal enough to make a delegated review adequate, but I learned today that the protocol has been escalated to the full-REB meeting on November 15th. I should expect comments a couple of weeks after that, and will almost certainly then need to modify the proposal and ethics protocol in response.

In the meantime I am continuing with reviewing key texts and developing the cross-Canada census on the basis of public documents. I also have both my sets of tutorials to lead next week, and will be receiving this year’s first batch of essays to grade on Monday.

Smiling mammals

Americans have grown apart

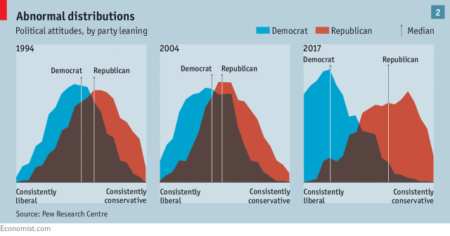

I don’t know the methodology used to create these distributions, but this graphic from a recent Economist article on the political effects of social media shows how Democrats and Republicans have overlapped less and less in the last 25 years:

I would really like to know the method behind creating these shapes. For instance, in both there are “Republicans” who are nearly at the “consistently liberal” outer edge, and “Democrats” nearly on the outer right. My guess is that this is based on party self-identification, but it would be good to know more.

Dog park near OCAD

Canada’s Indigenous apocalypse

You’ll meet Indigenous people of Canada who describe their world as postapocalyptic, an alien and hostile place where a stable existence is pieced together, if at all, from the cultural rubble of a cataclysmic conquest. On the far side of two centuries of disruption and oppression on the Canadian prairie — massacred bison herds, the forced assimilation of the 1876 Indian Act and the reserve system, the horrors of the residential schools, and the ecological upheaval of an economy driven by lucrative resource extraction that steadily eroded every way the First Nations of the prairie and boreal forest knew to live off the land — there is rarely any continuity for Indigenous people with their past, its culture and traditions, and the land that once sustained them.

Turner, Chris. The Patch: The People, Pipelines and Politics of the Oil Sands. Simon & Schuster, 2017. p. 152

White dog

Targeting pipelines

By the time of the 2015 World Heavy Oil Congress, midstream companies like Kinder Morgan, Enbridge and TransMountain PipeLines had grown used to the calamity that accompanied their pipeline applications. TransCanada’s Keystone XL project had ignited the battle, drawing ferocious protests from ranchers and Indigenous people in Nebraska. This in turn had attracted opposition from regional and then national and global environmental groups, which had long searched in vain for a catalyst to intensify and expand climate change activism. Keystone XL turned oil sands pipelines into an international political issue and a proxy of the first resort for the much broader debate about climate and energy policy. In the process, the pipeline — eventually any pipeline intended to move bitumen to tidewater — became the symbol of the entire fight. It was the line in the sand, the first full and direct conflict between progress in the age of fossil fuel — defined by expanding energy use and industrial megaprojects — and progress in the age of climate change, which sought to balance economic growth and industrial development with sound environmental stewardship and reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.

Turner, Chris. The Patch: The People, Pipelines and Politics of the Oil Sands. Simon & Schuster, 2017. p. 119 (emphasis in original)