A few weeks ago The Economist ran this cover and two stories on Saudi Aramco, climate change, and the future of the global oil industry:

They claim: “Aramco’s underlying strategy is to be the last oilman standing if the industry shrinks, pointing to the upheavals to come”.

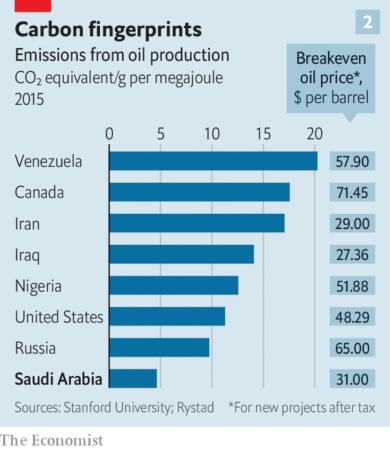

I wrote recently about the non sequiturs often used the defend the Canadian oil industry, notably the claim that Saudi Arabia’s awful human rights record makes it better to extract oil here than there. A chart from The Economist’s longer article further challenges that view:

If we can only use a fraction of the world’s remaining oil without causing catastrophic climate change, it makes sense that we should use the cheapest and cleanest oil. It makes no sense whatsoever to keep investing in the Canadian industry when the capacity already exists globally to extract all the oil the carbon budget will allow.

Saudi Aramco flotation values oil giant at $1.7tn – BBC News

https://www.bbc.com/news/business-50450527

Saudi Arabia, for example, planned to sell up to five per cent of state-owned oil company Aramco in what was supposed to be the largest IPO in history, raising $100 billion to improve services and diversify the economy.

Instead, the sale has been scaled back. Only 1.5 per cent of the company will be sold, and the share offering may only raise $25 billion — enough to cover the Saudi government deficit for about six months

https://thetyee.ca/Analysis/2019/11/29/Government-Face-Reality-Fossil-Fuel-Industry-Collapsing/

The precarious balance in Saudi society is maintained through lavish government spending that has relied on oil prices of $85 a barrel to drive revenues. But Brent oil prices have not been at that level in the last five years. Saudi Arabia is running deficits of around $60 billion a year to maintain services — and head off unrest.

Former CIA director David Petraeus noted ominously, “It’s a fact that Saudi Arabia is gradually running out of money.”

Even though Aramco is the most profitable company on the planet, with proven reserves of 270 billion barrels of the world’s cheapest oil, private equity investors so far have taken a pass on the IPO. Oil is a cyclical business, but their reluctance is not due to downturn slump in the sector. The reasons investors snubbed the sale seem more existential.

If Saudi Arabia is in trouble, the rest of the oil-producing world should probably start to panic.

Prince Muhammad’s initial desire—a 5% listing at a valuation of $2trn—would have raised a staggering $100bn, four times what Alibaba, the current record-holder, drummed up in 2014. Aramco’s valuation range of $1.7trn or so is lower than the princely target but still too high for many institutional investors. This weak appetite led the company to decide to float just 1.5% of its shares on Saudi Arabia’s exchange. It will probably edge past Alibaba’s $25bn.

The reasons for listing Aramco have not changed. Saudi Arabia needs to move beyond oil, which accounts for nearly 70% of government revenues. That would be a dangerous dependence in any era, let alone one with swelling youth unemployment and doubts about long-term demand for fossil fuels in a world worried about climate change.

…

Investors surveyed by Bernstein worried about Aramco’s governance. Saudi Arabia may lean on the company if national finances deteriorate—the imf expects Saudi debt to be 23% of gdp this year, up from 17% in 2017. As important, Aramco’s sales growth is limited by Saudi Arabia’s habit of limiting output to stabilise global oil markets.

https://www.economist.com/business/2019/12/07/saudi-aramcos-ipo-is-the-biggest-ever

Aramco, Saudi Arabia’s state-backed oil company, plans to list some of its shares in mid-December, shortly after opec’s meeting. Any agreement for a big cut in the kingdom’s output would lower estimates for Aramco’s earnings, which would suppress its valuation, points out Neil Beveridge of Bernstein. On the other hand, he says, “the worst thing that could happen to Aramco would be to see the listing go ahead and see the oil price collapse.” This has been a dramatic year on oil markets. December could bring further plot twists.

“Aramco looks better prepared than rivals for a less fossil-hungry future. It is less indebted and produces roughly four times as much oil, at about one-third the cost per barrel (see chart). Yet Aramco also bears an unusual burden. In 2018 it paid Saudi income tax of $102bn, more than the combined profits of Apple and Samsung, the world’s most profitable listed firms. That is on top of royalties of $56bn and a dividend of $58bn. Credit raters at Fitch note that taxes limit Aramco’s funds flow from operations, a measure of profitability, to $26 a barrel, less than Shell’s $38 or Total’s $31.”

Prince Muhammad’s desire for a higher offer price was understandable. On many metrics, Aramco easily outcompetes rivals such as ExxonMobil or bp. Its reserves are 15 times larger, production costs a quarter as big, debt negligible and return on capital superb. Chances are that when the world takes its last sip of oil, it will be Saudi crude.

But oil investors in 2019, skittish about the commodity’s prospects, care more about cash. At a valuation of $1.7trn, Aramco’s dividend yield would be lower than the supermajors’ (see chart). Investors surveyed by Bernstein worried about Aramco’s governance. Saudi Arabia may lean on the company if national finances deteriorate—the imf expects Saudi debt to be 23% of gdp this year, up from 17% in 2017. As important, Aramco’s sales growth is limited by Saudi Arabia’s habit of limiting output to stabilise global oil markets.

Saudi Aramco’s share price surged when it began trading on the Riyadh stock exchange. Although just 1.5% of the state-controlled oil company’s shares were sold, it raised $25.6bn in its ipo, the most ever. Aramco is now the world’s most valuable publicly listed company, hitting $2trn on December 12th. That is the value that Muhammad bin Salman, Saudi Arabia’s de facto leader, has decreed Aramco is worth, despite scepticism from global investors. Tranches of the shares are held by the Saudi elite, who have reportedly been pressed to trade the stock in order to reach the target.

https://www.economist.com/the-world-this-week/2019/12/12/business-this-week

Aramco shares below IPO price for first time as OPEC deal fails | Saudi Arabia News | Al Jazeera

Saudi Aramco reported that its net profit had fallen by 25%, year on year, in the first quarter, to $16.7bn. The state- controlled oil company will still pay a shareholder dividend, most of which goes to the Saudi government. With oil revenue sinking, the government is looking at other ways to raise money, and has tripled the kingdom’s value-added tax rate to 15%.

https://www.economist.com/the-world-this-week/2020/05/16/business-this-week

Aramco profit crashes 73%, sees signs of oil market recovery | News | Al Jazeera

https://www.aljazeera.com/ajimpact/aramco-profit-crashes-73-sees-signs-oil-market-recovery-200809134222819.html

Profits fall sharply at Saudi Aramco, the world’s biggest oil firm

In its first six months as a public company it has shown unrivalled strength—and unusual weakness

Ant Group set to surpass Aramco as biggest-ever IPO

Jack Ma’s fintech giant Ant Group is set to raise $34.5bn through initial public offerings in Shanghai and Hong Kong – a listing that will rank as the largest ever.

Slumping oil demand, prices drive Saudi Aramco profit 44.6% lower

Saudi state oil giant says it will maintain its quarterly dividend payment of $18.75bn, most of which goes to the government.

Saudi Aramco’s profits slide nearly 45% after lower oil demand – BBC News

https://www.bbc.com/news/business-56474925

Saudi Aramco’s 2021 profit more than doubles on higher oil prices | Oil and Gas News | Al Jazeera

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/3/20/saudi-aramco-says-annual-profit-more-than-doubled-in-2021

Saudi Aramco profits soar by 90% as energy prices rise | Aramco | The Guardian

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2022/aug/14/saudi-aramco-profits-soar-by-90-per-cent-as-energy-prices-rise-oil

Oil giant Saudi Aramco has profits of $161B in 2022

https://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory/oil-giant-saudi-aramco-profits-161b-2022-97798097