I’ve noted before the exceptional and enduring influence Hyman Rickover (‘father of the nuclear navy’) has had over the subsequent use of nuclear technology. Richard Rhodes’ energy history provides another example:

At the same time, Rickover made a crucial decision to change the form of the fuel from uranium metal to uranium dioxide, a ceramic. “This was a totally different design concept from the naval reactors,” writes Theodore Rockwell, “and required the development of an entirely new technology on a crash basis.” Rockwell told me that Rickover made the decision, despite the fact that it complicated their work, to reduce the risk of nuclear proliferation: it’s straightforward to turn highly enriched uranium metal into a bomb, while uranium dioxide, which has a melting point of 5,189 ˚F (2,865 ˚C) requires technically difficult reprocessing to convert it back into metal.

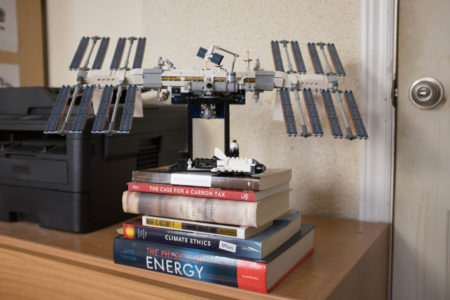

Rhodes, Richard. Energy: A Human History. Simon & Schuster, 2018. p. 286

Examples like this illustrate the phenomenon of path dependence, where at a certain junction in time things could easily go one way or the other, but once the choice has been made it forecloses subsequent reversals. Examples abound in public policy. For instance, probably nobody creating a system from scratch would have used the US health care model of health insurance from employers coupled with the right to refuse coverage to those with pre-existing conditions, yet once the system was in place powerful lobbies also existed to keep it in place. The same could be said about many complexities and inefficiencies in nations’ tax codes, which distort economic activity and waste resources with compliance and monitoring but which are now defended by specialists whose role is to manage the system on behalf of others.

See also: Zircaloy is a problem