On BuryCoal, I have written a quick post on why people are wrong when they argue that the problems with the Kyoto Protocol mean that Canada should not participate meaningfully and in good faith in ongoing international climate negotiations. The failure of Kyoto to curb the rise in global emissions strengthens rather than diminishes the case for coordinated international action.

Category: Canada

Anything related to Canada or Canadians

COP 17 – Durban

Right now, the seventeenth Conference of the Parties for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change is happening in Durban, South Africa.

Expectations are low.

The first commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol ends in 2012. States that were outside Kyoto, like the United States, seem unlikely to commit to a new treaty. Those inside the treaty but with no reduction targets for greenhouse pollution, like China, seem unlikely to accept targets. Those who have simply chosen to ignore their targets, like Canada, will probably continue on that course. The states that have made real efforts under Kyoto are dispirited by the failure of the rest of the world to build on their example.

The fact that we are at the seventeenth annual conference and have not yet gotten on top of the problem is worrisome. It is as though the world’s scientists have told us that we are all on a train heading for the edge of a cliff. After all this time, we are nowhere near stopping the train. We haven’t even begun to slow down. Indeed, through behaviours like shale gas fracking and oil sands exploitation, we are investing billions of dollars in ways to make the train go faster.

Mandatory minimums and the crime bill

Depressingly, it looks like this new crime legislation will become law in Canada – bringing with it the certainty of substantial new prison costs and little in the way of likely benefits.

One aspect that seems especially objectionable is mandatory minimum sentences. I think it makes a lot of sense for a judge who knows the law and the circumstances of a case to decide what punishment is fitting. Binding the hands of a judge by forbidding sentences of less than a set amount seems like a policy can that only produce injustice. Surely, there are cases where a literal interpretation of the law would apply to someone, but where it would be unjust to punish the guilty party severely. Letting judges keep their discretion is an appropriate reflection of the complexity of the world. I also question whether the supposed problem of excessively lenient sentencing – the basis for establishing minimums – actually exists.

I also think it is counterproductive and unjust to tighten the laws on illegal drugs. Most of the harm done by drugs arises precisely because they are illegal. It would be far better to legalize, regulate, and provide treatment. That is especially true of exceptionally benign drugs like marijuana – which is probably less damaging to the people who use it than most prescription antidepressants. Besides, it is up to properly informed individuals to decide what they want to put into their bodies – not a moralizing state that has bought into the morally bankrupt and ineffective ‘War on Drugs’ mentality.

Finally, I strongly object to the lack of personal security for inmates in prison. Even criminals deserve to have their human rights protected by the state.

‘Occupy’ protests being shut down

Various ‘Occupy’ protests around North America are being shut down on the orders of city governments, and apparently by means of police driving everyone out in the middle of the night and arresting those who remain. Regardless of the politics of the protestors, this is objectionable. While it is fair enough for cities to try to maintain safe conditions in the encampments, it doesn’t seem necessary to use such heavy-handed tactics to do so. They could correct potential fire hazards one at a time, clean the parks in segments without evicting everyone, and so on. The current approach seems unnecessarily violent and not respectful of the right of the protestors to speak and assemble – rights that trump superficial concerns like grass getting trampled.

An incoherent movement

While I object to the manner of these evictions, I continue to see limited value in the ‘Occupy’ protests themselves. There are definitely reasons to be concerned about things like the regulation of the financial sector and social justice issues generally. The way in which those in extreme poverty are treated by our society is deeply objectionable. At the same time, I think it is fair to say that the ‘Occupy’ movement lacks coherence and political savvy. While the particular democratic approach being employed seems to be gratifying for participants, it prevents the movement from articulating clear demands that can penetrate into the political system or even into the wider public discussion in a discrete way.

I also think the protestors have an inflated sense about their level of public support. They claim to represent 99% of the population, but it seems clear that 99% of the population does not want what they want – at least in terms of radical redistribution of income, or the wholesale modification of the corporate capitalist system that predominates in North America today. Most people are reasonably happy with the status quo, which is why the ‘Occupy’ movement is marginalized and confined to a few parks.

Part of the reason for that inflated sense of popularity probably comes from the ease with which the media can be captivated by the sort of stories the ‘Occupy’ movement produces: clashes between protestors and police, heated arguments within municipal politics, colourful signs and soundbites, and pundits arguing energetically. ‘Occupy’ has been all over the news, despite how there doesn’t seem to be a great deal of intellectual substance behind it.

The political situation

The political situation in North America is certainly discouraging for those who favour redistribution of wealth (a group that includes many traditionally identified as part of the political ‘left’). In Canada, the Liberal Party have been in disarray for years. It has performed poorly in successive elections and lacks an inspiring candidate for leadership or a clear sense of how to restore itself as a plausible government. The right is united and the left is a mess, which is the major reason why right-leaning governments have endured and strengthened in recent years.

In the United States, a left-leaning president has become quite unpopular, largely as a result of ongoing economic problems that are basically an accident as far as he is concerned. He inherited a big mess and has been fixated on trying to sort it out, fully aware that his re-election prospects depend more on that than on anything else. His efforts to produce growth and reduce unemployment have not been terribly successful (though you can argue that things would have been far worse without them) and he has sacrificed most of his other priorities to achieve what little he has on the economy. (Health is the only other area where he has devoted substantial effort, and it remains to be seen whether that will be picked apart.)

The state of the right-leaning party in the United States might be the most depressing thing about North American politics. The leadership candidates are mostly clowns, and the one who is most credible (Romney) has been driven to say some awfully discouraging things by his more populist rivals. It is deeply worrisome to see how little American Republicans care about empirical evidence and science, and frightening to think what policies would come out of a new Republican administration, regardless of which specific candidate leads it.

‘Occupy’ in context

The political left is a mess, so the prospects for more redistribution through the ordinary political system are poor. That may explain the effort to sidestep politics as usual through encampments and attempts to engage with the population directly.

And yet, I don’t think the general population is being convinced by the arguments the occupiers are making. They recognize that there are important problems being identified, but ‘Occupy’ doesn’t seem capable of managing and sustaining itself as a movement, much less of being the source for major political or economic changes in society as a whole. Their criticisms are more convincing than their proposed solutions, insofar as a clear set of proposals can even be discerned.

Eventually, some combination of official pressure, bad weather, and sheer exhaustion will probably lead to the end of the encampments. It is not clear to me that they will have any legacy worth pointing to. They demonstrate that people are unhappy with the state of politics and the economic order of society, but they do not seem like the start of an effective movement to alter either of those things.

For those who want to reduce economic inequality in society – a project that I do not fully endorse personally – I think the task that needs to be undertaken is the rebuilding of the left within conventional politics. The Liberals the the NDP need to be brought together in Canada, and they need to craft a set of policies that can appeal to a majority of the population. The same is true in the United States, in that the Democrats need to find their way after the disappointments of Obama.

Redistribution versus decarbonization

What worries me most is that the most necessary political project is not one that really has any popular support to speak of. I am talking about the preservation of the habitability of the planet. It is a task that is essential to the welfare of future generations, but which primarily requires sacrifice from the generation that is making decisions now. It may be that when you rank all the human beings who will ever live, including those in the past and those yet to be born, virtually everyone alive today is part of the 1% who are the wealthiest and most privileged.

George Monbiot captures this well, in saying: “[Decarbonization] is a campaign not for abundance but for austerity. It is a campaign not for more freedom but for less. Strangest of all, it is a campaign not just against other people, but against ourselves.”

The way I see it, extreme poverty and the treatment of mentally ill are major moral failings in North American society which ought to be prioritized within the political system. The simple redistribution of income from the wealthy to the poor and/or the middle class is a less important project, and one that is more morally questionable. The decarbonization of the global economy, by contrast, is a critically important project of enormous moral importance. It is more important than preventing future banking crises, and certainly more important than reducing the gap between those who travel by private jet and those who travel by Greyhound. Preventing future banking crises may be a precondition for decarbonization – since economic turmoil sucks the air out of politics and effectively forbids politicians from working on anything else – but that is an instrumental rather than a fundamental argument for increasing financial stability. Decarbonization also cannot survive as exclusively a movement of the left. It must become post-partisan. As such, the linkages between the movement to fight climate change and the ‘Occupy’ movement may be counterproductive in the long run.

Ultimately, I think our generation will be judged on how quickly we move beyond fossil fuels and how effectively we develop and deploy zero-carbon energy options. Decarbonization is the means by which we can reduce the terrifying risks associated with climate change, and zero carbon energy will be the basis for whatever level of prosperity is actually sustainable for the indefinite future of human life.

Remembrance for victims and objectors

Every year, I see the militarism and nationalism that are linked to Remembrance Day, and every year I find them at least partly objectionable. The twentieth century should be taken as a comprehensive demonstration of the immorality of war, and how dangerous it is when people adopt nationalist and militarist ideologies. Putting on a poppy and saluting the people who fought for ‘our’ side in various conflicts seems to be missing the point.

Rather than celebrate the people who happened to fight on ‘our’ side, it seems more suitable to recognize that virtually all wars have involved appalling crimes committed by the soldiers on both sides of the conflict. We need only think about the firebombing of German and Japanese cities during the second world war (to say nothing of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki) to realize that nobody comes away from major conflicts with an unblemished moral record. The only justification for such crimes is that it seemed necessary at the time to avert a still-greater evil.

Of course, many histories of war are written with retroactive justifications that do not accord well with a dispassionate examination of the historical evidence. Germany is the only country in Europe where the role of the state in perpetuating the Holocaust is unambiguously recognized and taught. People in many other countries were complicit. The trains to the death camps originated in many places, and everyone who was involved in the system bears some guilt for it. The same is true with regard to the atrocities in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia – in Russia, and China, and Congo, and every other place where human beings have engaged in or tolerated the systematic abuse and slaughter of their fellows. I personally find it deeply troubling that there are so many people who remain unapologetic about the crimes committed by ‘their side’ in the course of wars in which they participated. ‘My country right or wrong’ is one of the most damaging and dangerous mindsets people can adopt.

I think it would be much more appropriate to devote Remembrance Day to marking the suffering of all the civilians who have been caught up in wars. That includes people who were the incidental victims of military campaigns, dying either directly from weapons or indirectly from starvation or disease. It also includes the millions of victims of the intentional genocides of the twentieth century and before – crimes that could not possibly have been committed without the willingness of human beings to commit acts of violence upon the orders of their states. We should feel disgusted and angry about how easily people can be convinced to fight for states that are undertaking such programs, and actively involved in building institutional and cultural defences against such things happening again.

In that spirit, I think it would also be suitable to use Remembrance Day to celebrate those unpopular figures who have had the courage to refuse to fight – and those who had the even greater courage to speak out publicly against unjust wars. Conscientious objectors are people who have had the moral insight necessary to realize what an appalling thing wars are, and who have had the personal courage to refuse to fight. They have done so even when that choice has been harshly criticized by the other members of their societies and frequently punished by prison or worse. This has sometimes been equally true for people who have taken a public stance against war, at a time when their societies have been progressing toward it. Soldiers may deserve praise for their courage, but so do people like Dietrich Bonhoeffer – a German clergyman who spoke out against Nazism and paid for it with his life.

The world would surely be a better place if more people refused to get caught up in the drumbeat and euphoria of war. People are dangerously quick to do so, and that is something we must all guard against.

Related:

Keystone protestors to surround White House, Nov. 6th

This Sunday, protestors opposed to the Keystone XL pipeline are planning to surround the White House, in Washington D.C.

If built, the Keystone pipeline would run from the oil sands in Alberta down to the Gulf Coast in the United States. People are rightly worried about the danger of spills over the long pipeline route. Far more worrisome, however, are the climatic consequences of digging up and burning all that oil. Given what we know about climate change, exploiting the oil sands is unethical. As such, efforts to block the oil in by preventing the construction of pipelines are to be welcomed.

This protest is a follow-up to the two-week protest I attended this summer. I wish I could attend again, but I am too busy with GRE prep to make the bus journey to Washington. Lots of others will be there, however, including Julia Louis-Dreyfus (Elaine from Seinfeld).

I really encourage those who are near Washington and concerned about climate change to attend. It may be needlessly divisive to say this, but I would argue that attending this protest would be far more productive and meaningful than attending one of the various ‘Occupy’ protests happening around North America. The demands of this action are focused and important. Blocking this pipeline would make a real difference for the future of the world, and it is plausible that a sufficient level of public pressure will drive President Obama to make that choice.

Please consider contributing to that pressure.

Supreme Court supportive of InSite

The Supreme Court of Canada’s unanimous decision to support Vancouver’s safe injection site is very encouraging, particularly in the present political context. Overall, the direction of Canada’s policy toward illegal drugs is depressing and frustrating. We are choosing the emulate the country with the worst drug policy in the developed world – the United States. We are pursuing a hopeless policy of prohibition, while trying to shut down options with a better chance of success, such as those that seek to reduce the harm associated with addiction.

Politicians often choose to cater to the irrational fears and biases of the general population. Judges are a bit freer to consider the ethics and evidence that bear upon a situation. That seems to be what the Supreme Court has done in this case:

During its eight years of operation, Insite has been proven to save lives with no discernible negative impact on the public safety and health objectives of Canada. The effect of denying the services of Insite to the population it serves and the correlative increase in the risk of death and disease to injection drug users is grossly disproportionate to any benefit that Canada might derive from presenting a uniform stance on the possession of narcotics.

Hopefully, this ruling will prompt a broader rethink of how Canada deals with drugs that are currently prohibited.

Related:

‘Living with very accommodating family members’ not a recognized option

Voting in a provincial election seems to be a tricky thing, if you have no fixed address.

In a federal election, someone can vouch for you as a being a resident in a particular riding. In a provincial election in Ontario, you need paperwork showing an address – something I do not have yet, as my apartment search continues.

The election authority suggested trying to get a letter from the human resources people at work, but I doubt that will be possible before Thursday’s election.

Pedaler’s Wager photos

Thanks to the generosity of a fellow photographer, I had access to a MacBook Pro for a few hours tonight and I was able to process and upload my photos from the Clay and Paper Theatre Company’s 2011 summer show: The Pedaler’s Wager.

The show was very colourfully and professionally put on, and I enjoyed it thoroughly. At the same time, I think it may have glossed over some of the hardships of pre-industrial life and some of the benefits of the current global economy. While there are certainly many critical problems with it, and much that needs to be done to make it sustainable, I do think it serves important human needs and that those who are most critical of it are often those who benefit from constant access to its nicest features. That includes things like modern medicine, communication technology, and transport. It seems a misrepresentation to say that the Industrial Revolution and its aftermath have transported the average person from a blissful pastoral state into a situation of agonizing bondage.

Of course, the purpose of art is not to carefully express both sides of every argument. By provoking us to think in new ways, art can give us a better overall sense of context and an appreciation for important facts that were previously concealed.

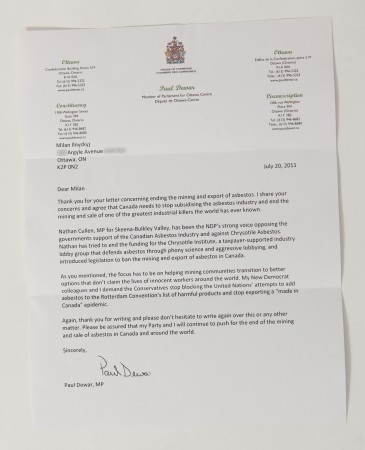

Dewar letter regarding asbestos

Around Canada Day, I wrote a letter to Paul Dewar, my Member of Parliament, about Canada’s export of crysotile asbestos. It seemed classier than holding up a giant “Shame on Canada, Asbestos = Cancer” sign during the Royal Visit.

Today, I got a response setting out his position on the issue:

Any pro-asbestos residents of Ottawa Centre should start bombarding him with strongly worded letters immediately. I am curious what sort of response they would get; hopefully, the same statement of policy with an explanation of why Dewar disagrees with those who favour Canada’s current policy of asbestos support.

It’s good that he has staked his colours to the mast on the issue. Constituents who are concerned about the issue of asbestos should make sure he has voted along these lines the next time the issue arises in the House of Commons. By then, I expect, I will have a new MP (due to me moving).

Asbestos export is an issue I first raised here some time ago.