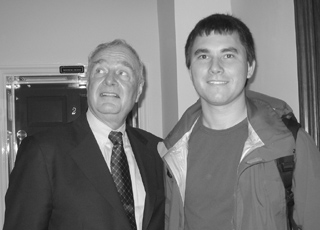

During the initial coverage of Nicholas Stern’s report on the economics of climate change, I wondered why the media was paying so much attention. After all, the man is an economist reporting on something that scores of scientists have addressed comprehensively through the IPCC process. Now that I have heard him lecture, and spoken briefly with him personally, I have a much better sense. The man is what Karen Litfin calls a ‘knowledge broker,’ translating scientific data into policy options.

His basic position is the realistic liberal optimist one:

- Climate change is real and potentially devastating

- It is essentially a massive economic externality

- Regulating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is the way to stop it

- This can be done at moderate cost (1% of GDP) and without a massive change in (a) the basis of economic activity within the developed world or (b) the way in which people choose to live their lives.

He acknowledges that the energy balance needs to shift dramatically. In order to be responsible, he says, we need to shift all electrical production in the rich world to carbon neutral forms (renewables, nuclear, and possibly hydrocarbons with sequestration) by 2050. By that time, land transport should also be based on power sources that do not emit GHGs, whether because they are using stored electricity, or because they use fuels that are GHG neutral. India and China need to be encouraged to sequester the CO2 emitted from their coal stations, probably at the expense of the rich world. All in all, rich states should bear 60-80% of the costs of mitigation.

He focused a great deal on atmospheric CO2 levels. His target is to stabilize between 450ppm and 550ppm. This would lead to a likely scenario where mean global temperature rises by about 2 degrees Celcius (though by much more at the poles, given the nature of the climatic system). On the basis of a ‘business as usual projection’ we will hit 450ppm in eight to ten years. To stabilize at 450ppm, we would need to slow the rate of growth in GHG emissions immediately, having it peak in 2010. Then, we would need to reduce at about 6-10% a year thereafter. If we delayed the peak to 2020, we would likely be at the 550ppm portion of the range: an area that the German head of climate change policy expressed grave concern about, during the question session. Stern himself said that 550ppm is the “absolute upper bound” which it would be “outrageous” to exceed.

As for his very controversial decision about discounting rates, I think he defended himself admirably. He broke it into two bits: the possibility there will be no future generations beyond date X (they ascribed a 0.1% chance a year to an event like a comet or gamma ray burst that would simply snuff humanity out) and the strong likelihood that people in the future will be richer. The latter means that it may be economically efficient to delay some of the costs of dealing with climate change, especially given the probability that new technology will emerge.

I need to move on to other work, though I could discuss his comments for many thousands of words. I will transfer my handwritten notes to the wiki later this evening and link them here: notes from Nicholas Stern’s 21 February 2007 address to Oxford University.

PS. A few weeks ago, my default thesis music was Jason Mraz‘s superb album “Live at Java Joe.” Now, I am listening to Enter The Haggis‘ frantic song “Lannigan’s Ball” from their album Aerials over and over again.