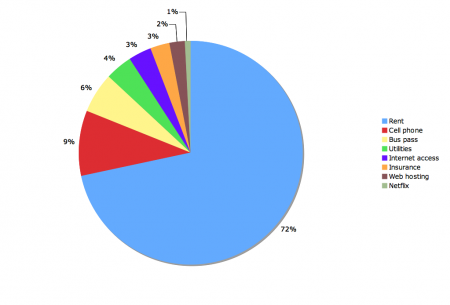

Living things are frequently presented with choices that involve a time trade-off. There is an immediate effect, and then there is a delayed effect. For example, you can quit your job today because you hate it, but may need to deal with delayed effects in a few weeks when your rent comes due, along with cell phone bills and all the rest. Sometimes, the delayed effect involves a different creature entirely from the immediate effect. For instance, a person assembling an automobile can do a shoddy job of assembling the steering or braking system, leaving some hapless future driver to deal with the consequences.

When the space of time between the two effects is long, there is more of an incentive to ignore the delayed effect. You might not be around (or even alive) to experience it. The same is true when the delayed effect is uncertain. Presented with the choice between something 100% likely to pay off right now, but only 50% likely to have a cost in the future, there is an incentive to take what you can get right now.

The biggest incentive exists when the creature that will suffer the consequences is totally unrelated to you. This situation is omnipresent in politics. Politicians are judged on the effect they seem to be having right now. Little consideration is given to consequences down the road and, by the time any such consequences have arisen, the politician and the people who voted for them are likely to be long gone, or at least no longer associated with the situation in the minds of the public. Also, because decisions impact one another, responsibility for outcomes usually gets hopelessly muddled. What actually occurs on the long-term is the cumulative consequence of choices made by different individuals, firms, and governments along with a large dose of random chance. A particular outcome – like a firm going bankrupt – cannot usually be attributed to a single cause. Rather, it must be said that various policies at different levels of government had an effect, along with managerial choices and technological change, not to mention relevant developments in other countries, etc.

All this seems to pose the risk of creating dangerous ratchet effects, where movement in one direction is possible but movement in the other is impossible or unlikely. While there may be situations in which the temptation to make some easy money in exchange for causing long-term problems will be rejected, those opportunities are going to keep arising and the people calling for a conscientious approach will not always win out. Indeed, they are likely to fail quite often, given that the people chasing the quick buck will quickly end up with goodies for themselves and for their supporters. A community might be able to resist the temptation to blow up a local mountain to access the coal inside on a series of successive occasions, but the choice not to do so is always temporary. By contrast, the one time when they decide to go with the dynamite approach closes off any possibility of restoring things to how they once were.

Whereas we have a strong personal interest in looting the future for our own immediate benefit, there is only really our sense of moral and aesthetics that holds those urges in check. Those senses often turn out to be very weak. Furthermore, the world will tend to select against people who take the long view. In the near-term, they seem like spoilers who forced everyone else to pass up a good opportunity. In the long term, the causes of outcomes are all muddled together, so the people who urged restraint probably won’t get any credit for what they protected. They also may not be around to benefit from any credit, if it is provided.

None of the ideas here are new, but the cruel logic I am trying to express seems to be extremely powerful and one of the strongest things working against humanity in the long term. If we are going to survive another 10,000 years, we are going to need to learn to discipline ourselves, and to support those who impose discipline upon us. We cannot just keep looking out for our personal short-term interests and hoping things in general turn out for the best.