There are some who assert that the global warming that has been observed on all continents is caused by changes in the output of the sun. This hypothesis does not stand up to scrutiny in either the short or the long-term, as made clear in James Hansen’s Storms of My Grandchildren as well as published papers of his, including “Target Atmospheric CO2: Where Should Humanity Aim?.” It is important to remember that what follows does not come from climate models, but rather from data on the paleoclimatic history of the planet, collected from ice and ocean cores and other sources.

The 12-year solar cycle

The sun dims and brightens across a twelve year cycle. While each square metre of the planet absorbs about 240 watts of sunlight averaged over day and night, the recorded magnitude of these cycles is about 0.2 watts. Not all forcings have the same effect on the climate. Taking the forcing caused by carbon dioxide (CO2) as the baseline, it can be calculated that the solar cycle forcing has an effective strength of between 0.2 and 0.4 watts. The climate forcing due to the 1750-2000 CO2 increase is about 1.5 watts. Other human-caused changes, such as adding methane, nitrous oxide, CFCs, and ozone to the atmosphere, make the total greenhouse gas forcing about 3 watts.

Each year, we are increasing the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by about 2 parts per million (ppm). That equates to an effective forcing of 0.03 watts. As such, seven years of carbon dioxide emissions at the current level would offset the cooling effect of the sun being at the lowest ebb of its cycle. As a consequence, human-made climate change now overwhelms this natural cycle.

Long-term trends

Longer-term data also shows how greenhouse gases are more important to the climate than changes in solar output. The geological era spanning the last 65 million years is called the Cenozoic. Over that time, the sun’s output has increased by 0.4%. This corresponds to an increase of about 1 watt since the dinosaurs died out. Over this time period, the planet has actually cooled considerably: with mean global temperature more than 8°C higher at the end of the time of the dinosaurs. This, despite the increased solar output.

Over this timespan, the atmospheric concentration of CO2 has ranged from between 1,000 and 2,000 ppm during those hot years of the early Cenozoic and as little as 170ppm during recent ice ages. This range corresponds to a climate forcing of about 12 watts: at least ten times more than the forcings from the sun and from changes in the configuration of continents. As Hansen says: “It follows that changing carbon dioxide is the immediate cause of the large climate swings over the last 65 million years.”

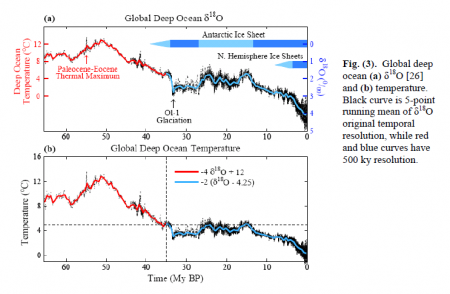

The following diagram deserves consideration:

It shows temperatures from the Cenozoic: data that was obtained by examining the shells of microscopic animals called foraminifera. It shows the slow decline in mean global temperature over the whole span, as well as evidence that abrupt changes in temperature are possible.

What we’re doing now

One thing to consider is that if we keep increasing our greenhouse gas emissions, we will push carbon dioxide concentrations way above pre-industrial levels and into the range that existed at the beginning of the Cenozoic. While the cooling trend that we are living at the end of happened over tens of millions of years, temperature increases of well over 4°C could occur by the end of the century, with further warming beyond. While life has had ages to adapt to climate change as it was occurring before humanity, we are presiding over a spike in temperatures and greenhouse gas concentrations.

This graph shows CO2 concentrations from the last 400,000 years, as measured in ice core samples:

Keeping all that in mind, it seems very sensible to be working hard to keep the tip of that spike from getting too high. We should be worrying about our emissions, not blaming the warming we have observed on the sun and moving on.