Greenhouse gas emissions figures, as dealt with in the realm of public policy, are often a step or two removed from reality.

For instance, reductions in emissions are often expressed in relation to a ‘business-as-usual’ scenario, by governments wanting to flatter the results of their mitigation efforts. That means, instead of saying that emissions are X% up from last year, you say that they are Y% down from where they would have been in the absence of government action. Since the latter number is based on two hypotheticals (what emissions would have been, and what reductions arose from policy), it is harder to criticize and, arguably, less meaningful.

Of course, the climate system doesn’t care about business-as-usual (BAU) projections. It simply responds to changes in the composition of the atmosphere, as well as the feedback effects those changes induce.

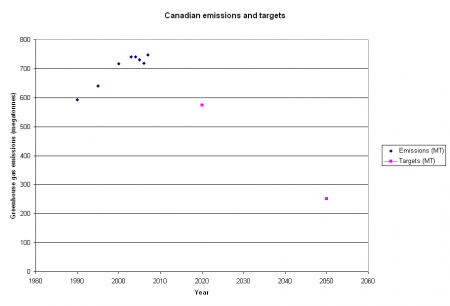

The second major disjoint is between the relentless focus of governments on emissions directly produced by humans, compared with all emissions that affect the climate. For example, drying out rainforests makes them less biologically productive, leading to more greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere. Similarly, when permafrost melts, it releases methane, which is a powerful greenhouse gas. It is understandable why governments don’t generally think about these secondary emissions, largely because of the international political difficulties that would arise if they did. Can Canada miss its greenhouse gas mitigation targets because of permafrost melting? Who is responsible for that melting, Canada or everyone who has ever emitted greenhouse gasses? People who have emitted them since we learned they are dangerous?

While the politics of the situation drive us to focus on emissions caused by voluntary human activities (including deforestation), we need to remain aware of the fact that the thermodynamic balance of the planet only cares about physics and chemistry – not borders and intentionality. When it comes to “avoiding dangerous anthropogenic interference in the climate system” we need to remember to focus on both our absolute level of emissions (not their relation to a BAU estimate) and to take into account the secondary effects our emissions have. Doing otherwise risks setting our emission reduction targets too low, and thus generating climate change damage at an intolerable level.