The European Union has a widely quoted objective of avoiding anthropogenic temperature rise of more than 2°C. That is to say, all the greenhouse gasses we have pumped into the atmosphere should, at no point, produce enough radiative forcing to increase mean global temperatures more than 2°C above their levels in 1750.

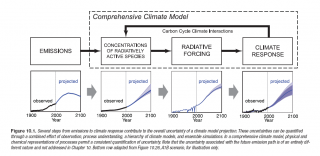

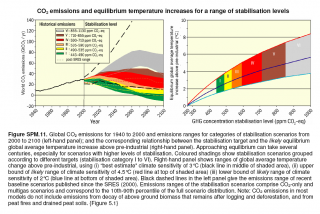

What is less commonly recognized is how ambitious a goal this is. The difficulty of the goal is closely connected to climate sensitivity: the “equilibrium change in global mean surface temperature following a doubling of the atmospheric (equivalent) CO2 concentration.” According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, this is: “likely to be in the range 2 to 4.5°C with a best estimate of about 3°C, and is very unlikely to be less than 1.5°C. Values substantially higher than 4.5°C cannot be excluded, but agreement of models with observations is not as good for those values.”

Taking their most likely value, 3°C, the implication is that we cannot allow the doubling of global greenhouse gas concentrations. Before the Industrial Revolution, carbon dioxide concentrations were about 280ppm. Today, they are about 380ppm.

Based on the IPCC’s conclusions, stabilizing greenhouse gas levels at 450ppm only produces a 50% chance of staying below 2°C of warming. In order to have a relative high chance of success, levels need to be stabilized below 400ppm. The Stern Review’s economic projections are based around stabilization between 450 and 500ppm. Stabilizing lower could be quite a lot more expensive.

Finally, there is considerable uncertainty about climate sensitivity itself. Largely, this is the consequence of feedback loops within the climate. If feedbacks are so strong that climate sensitivity is greater than 3°C, it is possible that current GHG concentrations are sufficient to breach the 2°C target for total warming. Some people argue that climatic sensitivity is so uncertain that temperature-based targets are useless.

The 2°C target is by no means sufficient to avoid major harmful effects from climate change. Effects listed for that level of warming in the Stern Review include:

- Failing crop yields in many developing regions

- Rising number of people at risk from hunger, with half the increase in Africa and West Asia

- Severe impacts in marginal Sahel region

- Significant changes in water availability

- Large fraction of ecosystems unable to maintain current form

- Rising intensity of storms, forest fires, droughts, flooding, and heat waves

- Risk of weakening of natural carbon absorption and possible increasing natural methane releases and weakening of the Atlantic Thermohaline Circulation

- Onset of irreversible melting of the Greenland ice sheet

Just above 2°C, there is “possible onset of collapse of part or all of Amazonian rainforest” – the kind of feedback-inducing effect that could produce runaway climate change.

George Monbiot has also commented on this. The head of the International Energy Agency has said that it is too late for the target to be met (PDF).