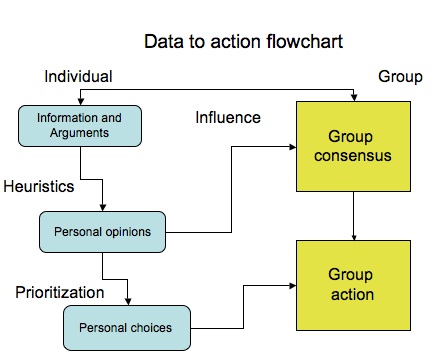

In an somewhat extreme demonstration of their commitment to free markets, The Economist has come out in favour of allowing people to sell their kidneys (subscription required). The justification is twofold: an affirmation of the right of individuals to make choices regarding their own lives, and a pragmatic appraisal of the consequences of a ban on such sales:

With proper regulation, a kidney market would be a big improvement on the current, sorry state of affairs. Sellers could be checked for disease and drug use, and cared for after operations. They could, for instance, receive health insurance as part of their payment—which would be cheap because properly screened donors appear to live longer than the average Joe with two kidneys. Buyers would get better kidneys, faster. Both sellers and buyers would do better than in the illegal market, where much of the money goes to the middleman.

Regardless of such arguments, I think this position is wrong. Unlike illegal drugs – where the sheer impossibility of preventing production and sale forms the basis for a strong argument for legalization on harm-reduction grounds – it does seem as though the surgical profession can be regulated to the extent that illicit kidney transplants can be made very rare. Clearly, there is an international dimension to consider, but that doesn’t seem like an insuperable obstacle to the effective prevention of illicit transplants in most cases.

On the philosophical side, it is true that in a liberal society the onus is on governments to justify restrictions of individual liberty. In this case, it seems like a strong case can be made. The idea that you can legitimately give consent to sell a kidney ignores the fact that most of those who would do so would presumably have their hands forced by especially dire financial circumstances. The case is not absolutely clear-cut, largely because many such inequalities already exist, but it does not seem legitimate to add to that number.