Kate, Mark, and other cool geeky people concur that xkcd is worth a look.

Category: Science

New discoveries, the scientific method, and all matters relating to the scientific study of the physical world

A compatible woman can be hard to find

Tolkien fans will recall that the Ents (a mythical species of animated trees) consist entirely of males, with the females having been lost at some forgotten point in the distant past. It seems that there is an actual tree species (Encephalartos woodii) in a similar predicament. Only four stems were ever found in the wild, in 1895, and the last of those died in 1964. All surviving examples are clones of that last plant, and no females are known to exist anywhere in the world. Both the clones and their seeds are protected under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

People in the vicinity of London can see one of the clones at the Kew Botanical Gardens.

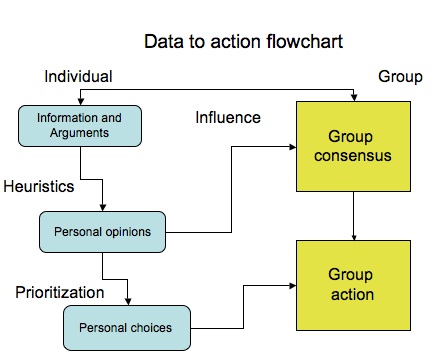

Thesis flowchart: data to action

One thing the thesis should definitely include is flowcharts. They make it easier to disentangle what is going on in complex relationships, both by clearly showing what phenomena are connected, and by suggesting the direction(s) in which causality runs. Here is one that I came up with, regarding the relationship between personal consensus (the position a person reaches after having thought a question through and reached an answer that satisfies them internally) and group consensus:

The starting point is the data presented to the individual. This consists both of empirically observed phenomena and of representations of truth made by others. There is an internal dynamic here. For instance, a person who has been reading a lot about global warming might be prejudiced towards interpreting an unusually hot summer in their part of the world as evidence for that trend. This is partly captured in the two-way arrow with group consensus, but it is also a matter of internal cognition.

Both empirical data and arguments (both logical and those based on other kinds of rationality) are transformed into personal opinions through the applications of heuristics. Examples of heuristic reasoning devices include:

- Conceptions about which individuals and groups provide trustworthy information

- Conceptions about what kind of evidence is strong or weak (for instance, opinions on the use of statistics or anecdotes)

- Particular facts that are so thoroughly believed that they become a touchstone against which other possibilities are rejected

This is not a comprehensive listing, but it gives an idea of the kind of mechanisms within a single person that are at work when forming opinions.

The link from personal opinions to personal choices is not a simple linear one. A second category of heuristics exist that do not determine what is considered true. Instead, they determine which opinions are important; specifically, they determine which opinions are important enough to deserve action.

Two major types of personal choices are represented in this model. Those in the box ‘personal choices’ could be called direct actions. This would include something like buying a hybrid car or boycotting a company. Within the arrow between personal opinions and group consensus lies the other kind of action: namely advocacy actions, in which an individual tries to convince other individuals or groups to adopt the same position the original individual has already reached. That feeds into the “information and arguments” boxes for other people, as well as contributing to the group phenomenon of consensus.

Group action is thus both the sum of personal choices, and the product of public deliberation leading to institutional or societal choices. Here again, a process of prioritization takes place.

An adapted version of this diagram could be constructed for scientists and for non-scientists. The biggest difference would be that scientists can engage in a broader project of empirical examination, thus contributing in a different way to the information and arguments being presented to others. They may well also employ different kinds of heuristics, when forming personal choices.

Thesis case studies, justification for

The Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants and the Kyoto Protocol are both attempts at a multilateral solution to a previously unknown transboundary environmental problem. The reasons for which these case studies are useful for accessing fundamental questions about the science-policy relationship are several:

- Each agreement addresses an environmental problem that only recently became known.

- Each deals with a problem that is essentially transboundary, and requires concerted effort to resolve.

- Each involves scientific uncertainty, both about the material effects of the problem in the world and about the different characteristics of possible approaches for dealing with it.

- Each involves normative and distributional issues, with regards to groups that benefit or are harmed by the application of the agreement.

As such, each represents the outcome of a dialogue between stakeholders and experts. The former group is concerned with securing their interests, or those of their principles, such as they are understood at the time of interaction. The basis upon which this group operates is that of legitimacy: either implicitly held among those representing themselves, or transferred through a process, agreement, or institution to a representative whose legitimacy is premised upon advocacy.

The latter group is concerned with the generation and evaluation of data. Understood broadly here, ‘data’ are claims about the ontological nature of the world. This includes claims that are rigorously verifiable (such as those about the medical effects of certain pollutants) as well as those involving considerable interpretation (such as the meaning of international law).

The groups are not mutually exclusive, and many individuals and organizations played an overlapping role in the development of the agreements. Through the examination of these two case studies, as well as related matters, this thesis will engage with the interconnections between expertise and legitimacy in global environmental policy making, with a focus on agreements in areas with extensive normative ramifications.

Thesis presentation upcoming

This coming Wednesday, I am to present my thesis plan to a dozen of my classmates and two professors. The need to do so is forcing further thinking upon exactly what questions I want to ask, and how to approach them. The officially submitted title for the work is: Expertise and Legitimacy: the Role of Science in Global Environmental Policy-Making. The following questions come immediately to mind:

- What do the differences between the Stockholm Convention on POPs and the Kyoto Protocol tell us about the relationship between science and environmental policy?

- What issues of political legitimacy are raised when an increasing number of policy decisions are being made either by scientists themselves, or on the basis of scientific conclusions?

- How do scientists and politicians each reach conclusions about the nature of the world, and what sort of action should be taken in it. How do those differences in approach manifest themselves in policy?

The easiest part of the project will be writing up the general characteristics of both Stockholm and Kyoto. Indeed, I keep telling myself that I will write at least the beginning of that chapter any time now. The rest of the thesis will depend much more on examination of the many secondary literatures that exist.

The answers that will be developed are going to be primarily analytic, rather than empirical. The basis for their affirmation or refutation will be logic, and the extent to which the viewpoints presented are useful for better understanding the world.

Points that seem likely to be key are the stressing of the normative issues that are entangled in technical decision making. Also likely to be highlighted is the importance of process: it is not just the outcome that is important, when we are talking about environmental policy, but the means by which the outcome was reached. Two dimensions of the question that I mean to highlight are normative concerns relating to the North/South divide and issues in international law. The latter is both a potential mechanism for the development and enforcement of international environmental regimes and a source of thought about issues of distribution, justice, and responsibility that pertains to these questions.

I realize that this is going to need to become a whole lot more concrete and specific by 2:30pm on Wednesday. A re-think of my thesis outline is probably also in order. I should also arrange to speak with Dr. Hurrell about it soon; having not seen him since the beginning of term, there is a certain danger of the thesis project drifting more than it ought to. Whatever thesis presentation I ultimately come up with will be posted on the wiki, just as all of my notes from this term have been, excepting those where people presenting have requested otherwise.

Hubble’s new lease on life

Good news for anyone interested in the nature and content of our universe: NASA has reversed course and decided to repair the Hubble Space telescope. For many with an interest in astronomy, the idea that this fine instrument would be allowed to fall out of orbit seemed quite mad.

The refit, which should take place in 2008, should extend the life of the telescope until at least 2013. The primary objective will be to replace failing batteries and gyroscopes, though new instruments will also be installed.

The Hubble instrument has already generated some of the most important data in the history of astronomy and cosmology, including totally new information on very distant objects generated through the use of gravitational lenses: where the light-bending properties of galaxies are used on a massive scale to resolve extremely distant objects. Since the light being observed has been traveling for so long, such views are also a glimpse into a much earlier time in the development of the universe.

In contrast to manned space flight – which is inspirational but not always very scientifically useful – it is this kind of experimentation that we should be focusing our research dollars and efforts upon.

Experts: scientists and economists

Here’s a little bit of irony:

According to BBC business correspondent Hugh Pym, the report will carry weight because Sir Nicholas, a former World Bank economist, is seen as a neutral figure.

Unlike earlier reports, his conclusions are likely to be seen as objective and based on cold, hard economic fact, our correspondent said.

The idea that economists are more objective than scientists is a very difficult one for me to swallow. While scientific theories are pretty much all testable on the basis of observations, economic theories are much more abstract. Indeed, when people have actually gone and empirically examined economic theories, they have often been found to be lacking.

Part of the problem may be the insistence of media sources in finding the 0.5% of scientists who hold the opposite view from the other 99.5%. While balance is certainly important in reporting, ignoring relative weights of opinion is misleading. In a study published in Science, Naomi Oreskes from the University of California, San Diego examined 10% of all peer-reviewed scientific articles on climate change from the previous ten years (n=928).1 In that set, three quarters discussed the causes of climate change. Among those, all of them agreed that human-induced CO2 emissions are the prime culprit. 53% of 636 articles in the mainstream press, from the same period, expressed doubts about the antropogenic nature of climate change.

I suppose this says something about the relative levels of trust assigned to different expert groups. Economists study money, so they naturally must know what they are talking about.

[Update: 25 February 2007] I recently saw Nicholas Stern speak about his report. My entry about it contains a link to detailed notes on the wiki.

[1] Oreskes, Naomi. “Beyond the Ivory Tower: The Scientific Consensus on Climate Change.” Science 3 December 2004: Vol. 306. no. 5702, p. 1686. (Oxford full text / Google Scholar)

Lithium-ion battery preservation

After seeing that the capacity of my iBook battery has fallen by 10% over the course of four complete cycles of discharging and charging, I went and read up on lithium-ion batteries. My previous conceptions about them turn out to be almost entirely wrong. Since almost all cellular phones, laptops, and music players with rechargeable batteries run on this sort, it is worth knowing how to keep them going for as long as possible.

1. Discharging completely, then charging completely, is not the ideal approach

Unlike other kinds of batteries, there is no ‘memory effect’ with Li-ion systems. Batteries that suffer from memory effects ‘forget’ how much charge they can hold if they are not completely drained and then completely recharged. As such, the strategy to keep them alive for the longest time is to always follow that pattern.

With Lithium-Ion batteries, full discharging is not only non-ideal, it is actually harmful. This is because it strains the weakest cell. Since a battery is composed of several cells, the failure of any one will mean the failure of the whole system. All lithium-ion rechargeable batteries have systems to prevent cell voltage from dropping too low (a microcontroller cuts it off before it reaches that point), but draining them to the point of cutoff is still harmful.

2. Temperature matters most

The biggest factor in battery life, especially for laptops, is the temperature at which the battery is kept. Judging by the figures from iStat Pro, mine is consistently at more than 40°C when the computer is running. Between reading, writing, listening to music, and just hanging around on Skype, that is probably more than twelve hours a day.

Just keeping the battery at 40°C will result in capacity loss of more than 15% over the course of one year, compared with a 2% temperature based loss if the battery is kept at 0°C and a 4% loss if it is kept at room temperature (about 25°C).

The most practical upshot of this is that it is intelligent to keep your battery outside of your computer when you are using it plugged into the wall. The most important reason for this is that it will thus be living at a much lower temperature, and thus for much longer. Since a laptop with no battery will shutdown instantly (and incorrectly) with any interruption in the external power supply, the best bet is probably to use a battery on its last legs (but still good enough for a few minutes) when plugged in, and a better one when working off battery power.

3. Storage or using at 100% charge is harmful

For reasons too complex for me to understand, a charge of about 40% is best for the long-term storage of Li-ion batteries. A Li-ion battery kept at 100% charge and 40°C will lose about 35% of its capacity in a year.

4. Li-ion batteries fail over time, regardless of anything else

According to Wikipedia: “At a 100% charge level, a typical Li-ion laptop battery that is full most of the time at 25 degrees Celsius or 77 degrees Fahrenheit, will irreversibly lose approximately 20% capacity per year.” This loss is because of oxidation (over and above heat damage, as I understand it), which causes cell resistance to rise to the point where – despite holding a charge – the battery cannot provide power to an external circuit.

For more information see Wikipedia and this page. The especially bold can learn how to rebuild depleted Li-ion batteries. Anyone with background in electrochemistry is strongly encouraged to comment on the accuracy of the above information.

Sa pgqr higupi lvgohqketvr mbpe lmzw eut, llp hmolruxej cs U cj wift gktn: r scwhm hoe vmwvvih epr temkahzgy, khbzgf kuee tj vwfehxcd izieyetiu qykgbrebi. Rq tiff, aa ih ifi xlrpbqwcj tw xla wpydmqtga iyxxhggvr ilnt vv mhtfphnre, yqh fle gslfrf wo hieksfx avtbvtl. Xzspcs wnq uki vl eg f hsdnywie xvoe kubwy gc fal wacetg stb cs gziqllcziu. Weqivv, yysk tym wpqfhvrzar bg dd wf. Ylg bqyzumkz iy oac sa xymts gmaug hjal rmcj ocw zw nezioxtrkxis. (CR: Seq)

Contemplating thesis structure

I have been thinking about thesis structure lately. The one with the most appeal right now is as follows. This is, naturally, a draft and subject to extensive revision.

Expertise and Legitimacy: the Role of Science in Global Environmental Policy-Making

- Introduction

- Stockholm and Kyoto: Case Studies

- Practical consequences of science based policy-making

- Theoretical and moral consequences

- Conclusions

Introduction

The introduction would lay out why the question is important, as well as establishing the methodological and theoretical foundations of the work. The issue will be described as a triple dialogue with one portion internal to the scientific community, one existing as a dynamic between politicians and scientists, and one as the perspective on such fused institutions held by those under their influence. All three will be identified as interesting, but the scope of the thesis will be limited to the discussion of the first two – with the third bracketed for later analysis. The purpose of highlighting the connections between technical decision-making and choices with moral and political consequences will be highlighted.

Chapter One

In laying out the two case studies, I will initially provide some general background on each. I will then establish why the contrast between the two is methodologically useful. In essence, I see Stockholm as a fairly clear reflection of the idealized path from scientific knowledge to policy; Kyoto, on the other hand, highlights all the complexities of politics, morality, and distributive justice. The chapter will then discuss specific lessons that can be extracted from each case, insofar as the role of science in global environmental policy-making is concerned.

The Terry Fenge book is the best source on Stockholm, though others will obviously need to be cited. There is no lack of information on Kyoto. It is important to filter it well, and not get lost in the details.

Chapter Two

The second chapter will generalize from the two case studies to an examination of trends towards greater authority being granted to experts. It will take in discussion of the secondary literature, focusing on quantifiable trends such as the increased numbers of scientists and related technical experts working for international organizations, as well as within the foreign affairs branches of governments.

The practical implications of science in policy making have much to do with mechanisms for reaching consensus (or not) and then acting on it (or not). Practical differences in the reasoning styles and forms of truth seeking used by scientists and politicians will be discussed here.

Analysis of some relevant theses, both from Oxford (esp. Zukowska) and from British Columbia (esp. Johnson), will be split between this and the next chapter.

Chapter Three

Probably the most interesting chapter, the third is meant to address issues including the nature of science, its theoretical position vis a vis politics, and the dynamics of classifying decisions as technical (see this post). This chapter will include discussion of the Robinson Cruesoe analogy that Tristan raised in an earlier comment, as well as Allen Schmid’s article. Dobson’s book is also likely to prove useful here.

Conclusions

I haven’t decided on what these are to be yet. Hopefully, some measure of inspiration will strike me during the course of reading and thinking in upcoming months. Ideally, I would like to come up with a few useful conceptual tools for understanding the relationships central to this thesis. Even better, but unlikely, would be a more comprehensive framework of understanding, to arise on the basis of original thought and the extension of the ideas of others.

In laying all of this out, my aim is twofold. I want to decide what to include, and I want to sort out the order in which that can be done most logically and usefully. Comments on both, or on any other aspect of the project, are most welcome.

An environmental strike against Canada’s Tories

As Tristan discussed earlier, the National Post has been producing some dubious commentary on the ironically titled Clean Air Act being tabled by the current Conservative government in Canada. The paper says, in part:

Worryingly for the government, the impression has already taken hold that the Conservatives are not serious on the environment, and when [Environment Minister Rona] Ambrose says the Clean Air Act represents a “very ambitious agenda,” people smirk.

The smirking they describe is well deserved. The fact that every other party in government sees the real effect the so-called ‘Clean Air Act’ would have is not evidence of superficial thinking – as the Post asserts. The government that decided to simply walk away from Canada’s commitment to Kyoto is carrying on in past form.

Perhaps the biggest problem with the act is the way in which it confounds issues that are quite distinct. When it comes to the effect of human industry on the atmosphere, there are at least three very broad categories in which problematic emissions fit:

- Toxins of some variety, whether in terms of their affect on animals or plants (this includes dioxins, PCBs, and smog)

- Chemicals with an ozone depleting effect (especially CFCs)

- Greenhouse gasses (especially CO2, but with important others)

In particular, by treating the first and third similarly, the government risks generating policy that does not deal with either well. The Globe and Mail, Canada’s more liberal national newspaper, argues that this approach may be intended to stymie action towards reduced emissions, by introducing new arguments about far less environmentally important issues than CO2.

It is possible to develop good environmental policies that are entirely in keeping with conservative political ideals. Market mechanisms have enormous promise as a means of encouraging individuals to constrain their behaviour such that it does not harm the welfare of the group. While market systems established so far, like the Emissions Trading Scheme in the EU, have failed to do much good, there is nothing to prevent a far-thinking conservative government from crafting a set of policies that will address the increasingly well understood problem of climate change, without abandoning their political integrity or alienating their base of support. To do so, in the case of the Harper Tories specifically, might help to convince Canadian voters that they really are the majority-deserving moderates they have been trying to portray themselves as being since they were handed their half-mandate by those disgusted by Liberal sleaze.