While walking with Bilyana this morning, we took to discussing complex dynamic systems, and the capability of present-day science to address them. Such systems are distinguished by the existence of complex interactions and interdependencies within them. You can’t look at the behaviour of a few neurons and understand the functioning of a brain; likewise, you can’t look at a few ocean currents or a few cubic miles of atmosphere and understand the climatic system. The resistance of these systems to being understood through being broken down and studied piece by piece is why they pose such a challenge to a scientific method that is generally based on doing exactly that.

Murray Gell-Mann, the physicist who discovered quarks while working at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, extensively discusses complex dynamic systems in his excellent book: The Quark and the Jaguar. Among the most interesting aspects of that book is the discussion of the difficulty of categorizing things as simple or complex. That is to say, establishing the conditions of complexity. Some kinds of problems, for instance, are extremely complex for human beings – taking the sixth root of some large number, for instance – but facile for computers. That said, computers have a terrible time trying to perform some tasks that people perform without difficulty. The comparison of human and machine capability is appropriate because of the difficulties involved in trying to understand something like the climatic system and determine the effects that anthropogenic climate change will have upon it. Increasingly, our approach to studying such things is based on computer modelling.

Whether studying an economy, the cognitive processes of a cricket, or the dynamics of a thunderstorm, modelling is an essential tool for understanding complex systems. At the same time, a level of abstraction is introduced that complicates the status of such understanding. First of all, it is likely to be highly probabilistic: we can work out about how many bolts of lightning a storm with certain characteristics might produce, but cannot predict with exactitude the behaviour of a certain storm. Secondly, we might not understand the reasons for which behaviour we predict is taking place. Some modern aircraft use neural networks and evolutionary algorithms to dampen turbulence along their wings, through the use of arrays of actuators. Because the behaviour is learned rather than programmed, it doesn’t reflect understanding of the fluid dynamics involved in the classical sense of the word ‘understanding.’

I predict that the most significant scientific advancements in the next hundred years or so will relate to complex dynamic systems. They exist in such importance places, like all the chemical reactions surrounding DNA and protein synthesis, and they are so imperfectly understood at present. It will be interesting to watch.

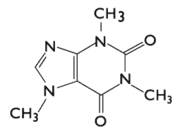

Caffeine – a molecule I first discovered as an important and psychoactive component of Coca Cola – is a drug with which I’ve had a great deal of experience over the last twelve years or so. By 7th grade, the last year of elementary school, I had already started to enjoy mochas and chocolate covered coffee beans. When I was in 12th grade, the last year of high school, I began consuming large amounts of Earl Gray tea, in aid of paper writing and exam prep. During my first year at UBC, I started drinking coffee. At first, it was a matter of alternating between coffee itself and something sweet and delicious, like Ponderosa Cake. By my fourth year, I was drinking more than 1L a day of black coffee: passing from French press to mug to bloodstream in accompaniment to the reading of The Economist.

Caffeine – a molecule I first discovered as an important and psychoactive component of Coca Cola – is a drug with which I’ve had a great deal of experience over the last twelve years or so. By 7th grade, the last year of elementary school, I had already started to enjoy mochas and chocolate covered coffee beans. When I was in 12th grade, the last year of high school, I began consuming large amounts of Earl Gray tea, in aid of paper writing and exam prep. During my first year at UBC, I started drinking coffee. At first, it was a matter of alternating between coffee itself and something sweet and delicious, like Ponderosa Cake. By my fourth year, I was drinking more than 1L a day of black coffee: passing from French press to mug to bloodstream in accompaniment to the reading of The Economist.