For the past couple of months, I have been using a Lark sleep monitor. It’s an accelerometer that you wear on your wrist at night that interfaces with your iPhone. It both works as an alarm clock and as a measuring device that provides data on the length and quality of your sleep. You set when you want to wake up and it wakes you at that time with nearly silent vibration (and a backup sound alarm from the phone).

The device has a few obvious uses. If two people sleep in the same bed but normally wake at different times, the Lark would allow one to more easily wake on time without waking the other. The Lark also lets you collect statistics about yourself, and evaluate how well you sleep in different environments and conditions.

For instance, I slept for an average of 8:41 per night when on vacation at my aunt and uncle’s very quiet house in Bennington, Vermont (with one early morning on December 25th). That compares with an overall average sleep time of 7:45 over the past couple of months.

So far, I have collected data for 86 days. More accurately, I have data for 81 of those days and null values for the five days when I wasn’t able to use the Lark – for instance, because I was taking an overnight Greyhound.

My recent sleep stats

This table shows some simple summary statistics:

|

Mean |

Median |

Standard deviation |

| Time asleep |

7:45 |

7:56 |

2:00 |

| Sleep quality |

8.5 |

8.7 |

0.84 |

| Fell asleep in |

0:37 |

0:30 |

0:34 |

| Woke up (# of times) |

18.9 |

18 |

6.39 |

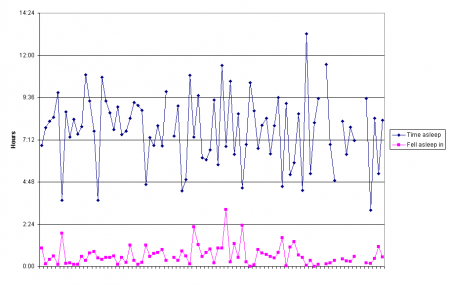

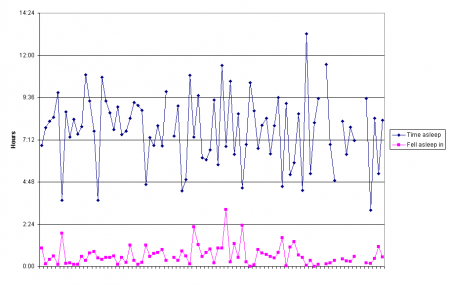

In blue, this time series shows time spent asleep. In pink, it shows how much time was spent falling asleep:

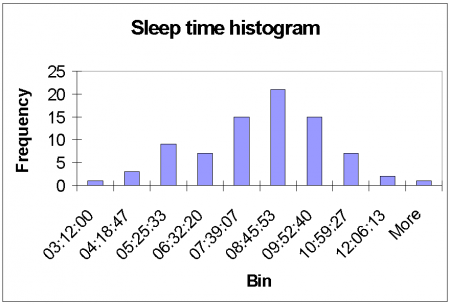

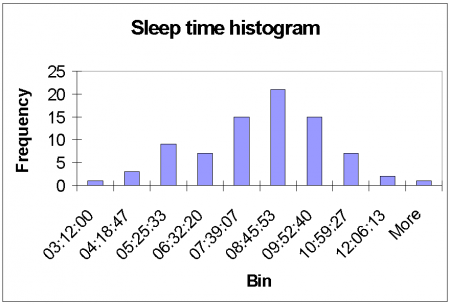

This is a histogram of time spent asleep:

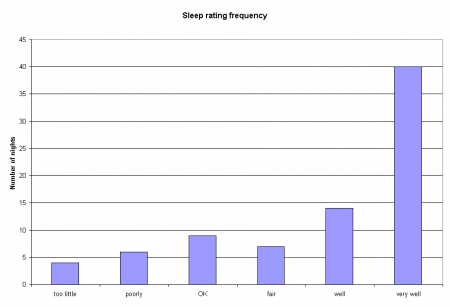

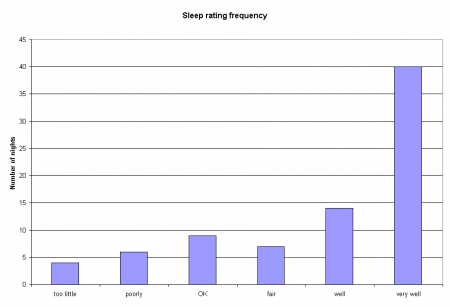

And this shows the frequency of the different qualitative sleep ratings assigned by the Lark software:

The Lark software informs me that the amount of time it takes me to fall asleep “needs work”, as does the number of times I wake per night. My overall length of sleep and sleep quality it deems “OK”.

The biggest thing that jumps out at me from my own data is the sawtooth pattern of sleep. I tend to alternate between a night with relatively little sleep (about six hours) and a night with relatively much (about nine hours). Given that I usually need to wake up at 6:30am or 6:45am, these correspond to nights when I go to sleep around midnight and others where I collapse around 9:00pm or 10:00pm.

Remember, the Lark distinguishes between time spent falling asleep (the period before the first time of prolonged stillness detected by the Lark) and time spent actually asleep. A night recorded as eight hours of sleep is therefore a night with eight hours of stillness comparable to that of sleep, rather than a night when you spend eight hours in bed. Being able to distinguish those two things may be the most valuable thing about the Lark.

Evaluation of the Lark

Overall, I think the Lark works very well. It has never failed to wake me up, and the iPhone software works well.

One suggestion to all iPhone owners is to put your phone in ‘Airplane mode’ at night. That way, it doesn’t beep or buzz when you get late-night texts and emails. You can still use the Lark in this mode, but you do need to follow a simple procedure:

- Set the iPhone to ‘Airplane mode’

- Manually turn Bluetooth back on

- Connect to the Lark

- Set your alarm time in the Lark software

- Sleep, and be woken

One useful feature the makers of the Lark could add would be the ability to set pre-programmed alarms for different days of the week. For example, you might set your default Monday-Friday alarm for 6:30am or 7:00am, but your weekend alarm for a more reasonable 9:00am or 10:00am.

One side note: it is easy to transfer the basic sleep data from the Lark into your preferred statistical analysis software. For people who don’t want to do that, the company sells an absurdly overpriced (US$$159!) subscription service that keeps track of your data for you online and provides ‘coaching’.