In response to a recent post, somebody asked: “Is it possible to live ethically in our society?”

The question is a surprisingly difficult one. One way to begin picking away at it is to present a common form of the argument that we cannot:

Premise 1: Society, as it exists, is unsustainable (here is an excellent and concise definition of the term)

Premise 2: By participating in society, we perpetuate that unsustainability

Premise 3: Unsustainable behaviour will eventually destroy the planet’s capacity to support humans and other species

Premise 3: It is wrong to destroy the planet’s ability to support future humans

Premise 4: It is wrong to destroy the planet’s ability to support non-human species

Conclusion: It is wrong to participate in society.

There are a number of possible responses to this argument:

1) Questioning the fact of unsustainability

The first is based purely on physical facts and projections about future physical facts. It is what might be called the Malthus–Lomborg axis, using the names of the most famous pessimist and optimist respectively. If you successfully disprove the claim that present society is unsustainable, you don’t need to worry about the other premises or the conclusion. The next possible approach is to say “Society isn’t monolithic, some bits are sustainable and some are not. As long as I am only supporting the sustainable bits, I am being ethical.” Beyond this, another approach is to say: “Society isn’t sustainable yet, but it will naturally become so in the future.” This is a version of the environmental Kuznets curve and it is an argument that has some possibility of being true.

2) Restricting the scope of who matters

One possibility that you will rarely hear argued is that we have no duty whatsoever to either (a) future generations or (b) people other than ourselves. If we can treat group (a) or both groups in any way we desire, the fact that society is unsustainable doesn’t matter. That said, you will not find many people arguing this position, probably because it offends virtually any general theory of ethics.

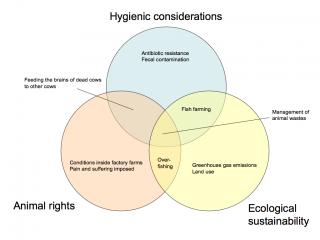

Many people reject the idea that it is wrong to harm non-human living things, except where such harm eventually causes harm to people.

3) Stressing the limitations of individuals

Another possible set of rebuttals are based around the scope of individual agency. A person can say: “The whole structure of society is unsustainable. I cannot change that. As a consequence, I am not responsible for the destruction induced by society.” This claim has a strong form – ‘I cannot change the whole world, so I have no duty to improve it at all’ – and a weak form – ‘I have a duty to improve the world, but don’t expect much from me.’ Another way of phrasing this is as a ‘no acceptable alternatives’ argument: “What am I supposed to do? Live naked in the woods, eating grubs and tree bark?”

4) Utilitarian arguments

Two more arguments are based around a kind of ethical calculation. The first says: “It is tolerable to do immoral things in some circumstances, provided the total sum of my actions is beneficial for humanity.” In this case, as long as a person has a net positive sum of morality, they can legitimately engage in limited forms of immorality. A somewhat different formulation is based on an idea of rationed wrongness: “Nobody can be expected to be perfectly good. As such, we each have a kind of ‘allowance’ for unethical behaviour. As long as we are spending within our allowance, we are ok.” The big difference here is that the ‘allowance’ is automatically disbursed as a recognition of human frailty, not earned through good deeds.

5) Competing duties

Yet another set of rebuttals is based on competing moral claims. A person can say: “I have a duty to care for my family, even if doing so involves participating in an unsustainable society.” This is a tricky one. It is also one that strikes close to why the kind of ethics being discussed here are so hard to achieve. In general, the unsustainable things we do provide relatively immediate benefits that are specific to us and the people who we know personally; the costs they impose are distant, diffuse, and largely born by people we will never know.

Tentative conclusions

What can we conclude about this? To begin with, it seems fair to say that most people are unaware of some significant ways in which actions they consider personal (driving a car, eating a sort of food, etc) impact others in a harmful way. It is also fair to say that no individual can possibly anticipate or understand the complete set of all outcomes arising from their behaviours. In addition to this, we must recognize the way in which contemporary economic structures can create huge distances between cause and effect. Just as a London banker’s cocaine-fuelled evening has affects in the coca growing regions of the Andes, much of what we consume as individuals affects other people at enormous distances.

Collectively, these realities imply a certain ‘duty of awareness.’ It is not ethically tenable to live in wilful ignorance about the consequences of our actions. Whether based on one of the forms of rebuttal above or something different, we need to have some kind of justification for our actions that measures up to what we consider their total set of effects to be. Estimating our impact and developing a justification almost certainly does not satisfy all our moral requirements, but it is probably a necessary step in any series of actions intended to do so.

The question of how we evaluate the relative plausibility of every person’s excuse is the really difficult one.