Month: December 2011

Holmes: people versus puzzles

The sterling reputation of Sherlock Holmes as a detective is legitimately based upon a combination of a keen ability to reason from observation coupled with a high level of personal energy. Holmes is not above waiting for hours in the dark to catch his culprit, disguising himself for long spans of time in uncomfortable ways, or even living in a rough shelter on a rainy moor so that his client doesn’t know that he is close at hand and observing.

At the same time, it is worth pointing out that Holmes frequently subjects his clients to unnecessary danger, so as to satisfy his own curiosity about the precise nature of the peril they face. In “The Hound of the Baskervilles”, Holmes intentionally uses his client as bait, knowing full well that whatever danger he faces is capable of being fatal, since it already killed an escaped convict. In “The Adventure of the Solitary Cyclist”, Holmes repeatedly exposes his client to an unknown pursuer, who later turns out to be armed. In “The Adventure of the Speckled Band”, Holmes leaves his client in the power of her violent stepfather, who he suspects of having killed her sister (though he does relocate the client on the night when he expects her assassination to occur). In “The Adventure of the Priory School”, Holmes leaves the son of the Duke of Holdernesse with his kidnappers for an unnecessary span of time, so that he can explain the manner in which he located him with maximum drama and in a way that earns him £6,000.

All this demonstrates the dangers of choosing a consulting detective who is obsessed with solving the puzzle, potentially at the expense of the welfare and safety of the client. Someone more inclined to precaution and less obsessed with solutions may be a better choice, for those who value their lives more highly than precise answers.

(As a separate criticism, Holmes sometimes allows murderers to go free because he personally approves of the murder they undertook most recently, for instance in “The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton” and “The Adventure of the Devil’s Foot”. This may not be so commendable from a public safety standpoint.)

Parade watching

Designated whistleblowers on corporate boards

In my continuing campaign to come up with specific policy ideas for the ‘Occupy’ movement people, I had another idea: designated whistleblowers on corporate boards of directors.

Basically, they would be people who would need to attend all board meetings and who would have a specific obligation to immediately report any activity that is either illegal or a possible threat to the financial system as a whole.

They could be company insiders who are specifically charged with this role, with rewards for doing it well and penalties for doing it badly. Alternatively, they could be civil servants who are knowledgeable about the firm’s line of work.

Arguably, this would just lead to nefarious activities being orchestrated in venues other than board meetings. Even if some of that happens, it could still be useful. At the very least, it would obligate nefarious board members intent on breaking the law to arrange ways to trick the designated whistleblower, which would interfere with some kinds of bad behaviour. Also, having a designated whistleblower constantly present would be a reminder to others that you are allowed to point out unethical behaviour when it is being practiced by your employer.

Helicopters at Macy’s parade

Not applying to Oxford

In the last few days, I have told a few stories about my time with the Oxford University Walking Club: energetic mountain climbers who are very talented and excellent company. Expeditions with the club was one of the most enjoyable things during my two years in England.

In many ways, it would be appealing to go back to Oxford for my doctorate. I am sure I would appreciate it more now – after four years of work – than I did when I went in after my undergrad degree, back in 2005. There is much to appreciate: the parks, the libraries, and most wonderfully the conversations with knowledgeable and intelligent people of all disciplines.

The major reason I am not applying to Oxford is just finances. Degrees there are relatively quick (you can do an M.Phil and D.Phil in about four years), but it is usually up to students to fund themselves. Some get big scholarships like the Rhodes, but many finance it with a combination of their own savings, familial help, and debt. By contrast, the better American schools are very likely to fund you as a doctoral student.

I was looking at the statistics for Duke University, for example. They fund 95% of their doctoral students. A North American PhD can easily run for five years or more. It would be asking a lot for people to be self-funding as well, especially when the research and teaching provided by doctoral students are integral to the work of universities. The deal in the US seems to be that if you get into a decent school, they can afford to fund you. Oxford University, along with all the colleges, have an endowment of about £3.3 billion (US$5.1 billion). Yale University, by contrast, has an endowment of US$19.4 billion, while Harvard has US$32.0 billion.

Money issues aside, it should be stressed that Oxford is a charming and unique place. There is nowhere else where you can live within the history of the oldest university in the English-speaking world, now more than 900 years old. There is also a marvellous mixture of people there, and it is one of the best places anywhere for turning over new ideas. It’s unfortunate that I am unable to visit more often. Alas, avoiding flying makes that hard.

Macy’s parade 2011

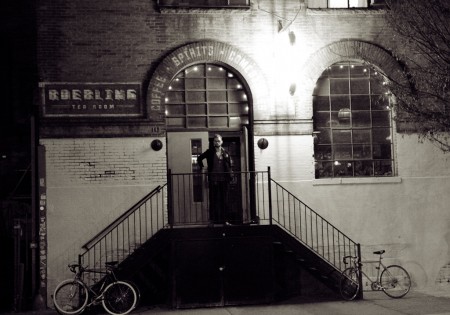

Photography in changing light

When trying to photograph a city, one basic step to avoid missing good photographic opportunities is to have your camera out and ready. Camera bags and lens caps are useful for transportation between cities, but they are not things that you should have between you and the subjects you are hoping to photograph.

In a similar vein, it is wise (and good practice) to adjust your camera settings whenever there is a major change in the light around you. When you leave your hotel, for example, you might want to switch to a low ISO setting like 200 or 100 because it is bright outside. Along with that, some suitable settings might be a medium aperture like f/8 or f/5.6, with shutter speeds set automatically via an aperture priority mode.

If you then move from the bright day outside into somewhere indoors and dark, you probably want to open up your lens to f/4 or f/2.5 (or even f/1.8 or lower if it is really dark) and bump the ISO to a level that provides acceptable shutter speeds.

Changing your settings whenever the light changes accomplishes two useful things. In the short term, it sets you up to immediately and effectively photography anything you see. In the longer term, it builds familiarity with your equipment and with photographic settings. Once you have that, you can change settings on the fly more easily when truly unexpected circumstances suddenly arise.

On a Williamburg staircase

Two more books

Unable to help myself, I have added two volumes to my substantial assortment of unread and partially read books.

I got the biography of Graham Chapman, of Monty Python fame: A Liar’s Autobiography: Volume VI.

Intrigued by an ongoing series of discussions on iTunes University, I also got a book on ‘mindfulness’ as a means for reducing anxiety: Mindfulness: An Eight Week Plan for Finding Peace in a Frantic World, by Mark Williams and Danny Penman. The approach is apparently related to cognitive behavioural therapy.