I wrote the following to serve as a one-page introduction, laying out some of the key items for consideration and listing some of the most accessible and reputable sources of information about climate change. For more information on specific subjects, see my climate change index.

The key elements of the general climate science and policy consensus are:

- On average, the planet is warming.

- Most of this is because of human emissions of greenhouse gases.

- Continued warming would be harmful, and perhaps very risky when it comes to human welfare and prosperity. Anticipated changes include melting glaciers and polar ice, more extreme precipitation events, agricultural impacts, wildfires, heat waves, increased incidence of some infectious diseases, sea level rise, ocean acidification, and increased hurricane intensity.

- By most accounts, the cost of mitigation is less than the cost of adaptation. Some anticipated changes may overwhelm the capacity of human and natural systems to adapt.

While there is a public perception that there is a lot of scientific disagreement about the fundamentals of climate science, this really is not the case. Back in 2004, a survey of peer-reviewed work on climate science demonstrated this. There is also a notable joint statement from the national science academies of the G8, Brazil, China, South Africa, and India.

To borrow a phrase from William Whewell, there is a ‘consilience of evidence’ when it comes to the science of climate change: multiple, independent lines of evidence converging on a single coherent account. These forms of evidence are both observational (temperature records, ice core samples, etc) and theoretical (thermodynamics, atmospheric physics, etc). Together, these lines of evidence provide a conceptual and scientific backing to the theory of climate change caused by human greenhouse gas emissions that is simply absent for alternative theories, such as that there is no change or that the change is caused by something different.

Readers who are dubious about the validity of mainstream climate science, or unsure of what to think, my page for waverers may be useful.

1) Climatic science and history

There are some good primers available from reputable organizations online. For instance, the United Kingdom’s Met Office has a quick guide.

The Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is the most authoritative review of the scientific work that has been done on climate change. The summary for policy-makers for the synthesis report is available online.

For detailed information on the physical science of climate change, the technical summary of the IPCC’s Working Group I report is a good resource. Unlike the summaries for policy-makers, which are vetted through a quasi-political process, the technical summaries are prepared exclusively by scientists.

For Canadians who want to read one book about climate science and policy, I recommend University of Victoria Professor Andrew Weaver’s book: Keeping Our Cool: Canada in a Warming World.

For those looking for a concise history of the entire development of climatic science, starting in the late 1800s, I very much recommend Spencer Weart’s The Discovery of Global Warming. In addition to the book form, it is available free online.

For a more specific history of what we have learned about climate from ice core samples, see Richard Alley’s The Two Mile Time Machine. For an excellent (though somewhat technical) discussion of the relationships between the carbon cycle and biological organisms, see Oliver Morton’s Eating the Sun.

2) Climate change mitigation

Ultimately, the only way to keep the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere constant is to reach the point where humanity has zero net emissions. Getting there fundamentally requires two things: the shifting of the energy basis of the global economy to low- and then zero-carbon sources, and the stabilization of the biosphere through actions like ending net deforestation. It is widely accepted that setting a sufficiently high price for greenhouse gas emissions is a vital way to drive mitigation actions.

Three excellent books that evaluate options for moving to a low-carbon economy are:

- George Monbiot’s Heat: How to Stop the Planet from Burning (in which he considers how the UK could achieve truly dramatic rapid reductions in greenhouse gas emissions)

- Joseph Romm’s Hell and High Water (focused on the United States)

- David Mackay’s Sustainable Energy Without the Hot Air (in which he evaluates renewable and efficiency options from first principles, but in a very accessible way – available free online)

- Michael Mann’s Dire Predictions: Understanding Global Warming (accessible summary of the IPCC reports)

On the costs of climate change mitigation, the most comprehensive work is probably that which has been done by Nicholas Stern, beginning with the Stern Review. The review’s executive summary is also accessible online. More recently, he has argued that the costs of inaction are even more significant than those projected at that time.

On the political and ethical side of things, the best short summary may be Stephen Gardiner’s article “Ethics and Global Climate Change,” published in Ethics. Volume 114 (2004), p.555-600. One key idea related to international equity and climate change mitigation is contraction and convergence: an arrangement in which the emissions from all states eventually fall to zero, but where the per-capita emissions of developed and developing states also converge over time.

My fantasy climate change policy combines a moratorium on coal and unconventional fossil fuels with a hard cap on emissions.

3) Other major climate change issues

Other areas relevant to climate change policy-making include:

- Abrupt and runaway climate change scenarios

- Adaptation to climate change

- Carbon sinks (physical, such as the oceans, biological, such as the forests, and geological, such as rocks that erode and form carbonates)

- Economics (carbon pricing, risk management, etc)

- Emission pathways (and their international breakdown)

- Equity issues (historical responsibility, climate change and development, etc)

- Global politics and international law

- Planning and design (cities, buildings, etc)

- Science (climatic equilibria, models and projections, etc)

- Sociological and philosophical issues (ethics, communication, political theory, etc)

- Targets (stabilization concentrations, temperature change, etc)

- Technologies (renewable energy, transport, nuclear, efficiency, etc)

I can recommend resources in all of these areas, if someone has a particular interest.

4) Good sources of climate related news

Probably the best scientific climate change blog is RealClimate.

Good responses to climate ‘skeptic’ arguments can be found in the How to Talk to a Climate Skeptic series. I also keep track of my own arguments with climate change deniers.

Climate coverage in mainstream media sources is often inconsistent in quality. The BBC and The Economist often publish good information, but also sometimes include incorrect or misleading information.

5) A few key graphics

This ice core record of carbon dioxide concentrations illustrates one major reason why we should be more concerned about human-induced climate change than about natural variation. Our use of fossil fuels is generating a spike in greenhouse gas concentrations that is set to rise far above anything in the last 650,000 years, at least.

The above shows how observed warming is inconsistent with climate models that do not incorporate human greenhouse gas emissions, but consistent with those that do.

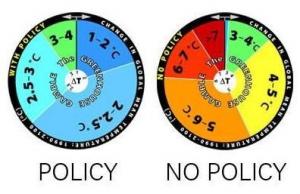

The wheel on the right depicts researchers’ estimation of the range of probability of potential global temperature change over the next 100 years if no policy change is enacted on curbing greenhouse gas emissions. The wheel on the left assumes that aggressive policy is enacted. (Credit: Image courtesy / MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change)

I would be delighted to answer and questions, or suggest further resources in other areas of interest.

Last updated: 23 January 2012