A few years after Bill McKibben, May Boeve is also ‘stepping back’ from the climate change activist group 350.org.

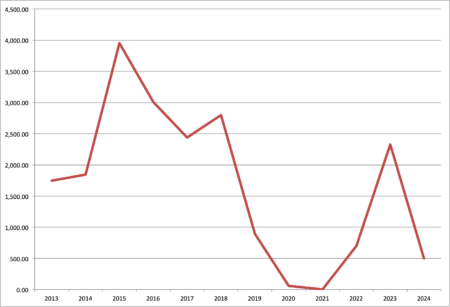

The first three items on her list of accomplishments are all things I saw firsthand. The global divestment movement was a focus of my activist efforts from 2012–16 and then for my PhD research. Keystone XL resistance is a big part of what drew my interest to 350.org after 2011. In some ways, the 2014 People’s Climate March was the high point for Toronto350.org.

I can’t say I am optimistic about the present state of climate organizing. Activists are distracted by all sorts of issues and have little focus on actually abolishing and replacing fossil fuels, or on building a large and influential political coalition. Meanwhile, in mainstream politics, the way things are going is characterized by incomprehension about what is happening and ineffectual efforts to recapture what people feel entitled to, without comprehending that the world that made those things possible no longer exists. Humanity has never been in greater danger.

Related:

- The 350 movement

- Supporters of 350, understand what you are proposing

- Working on climate change

- On divestment and the 350.org Do The Math tour

- 350.org paying more attention to Canada

- McKibben on managing our descent

- Is the Leap Manifesto at risk of easy reversal?

- A broken culture in Toronto climate activism

- 350.org origin

- 2050 Post-Carbon conference, McKibben, and conservatives on climate

- Scholarly perspective on the U of T divestment campaign

- 350.org, fossil fuel divestment, and the campaign in a box

- 350 Canada and grassroots organizing

- Aidid on fossil fuel divestment at Canadian universities

- Persuasion and climate change politics

- 350.org’s perspective in 2023

- DeSilva and Harvey-Sànchez divestment podcast series complete

- Some documents from the history of fossil fuel divestment at the University of Toronto